One of my earliest board gaming memories is a robotic voice ruthlessly mocking me and my brothers as we desperately race against a clock we cannot see to stop a rogue computer program. Let me tell you about The Omega Virus!

My brothers and I are very different people. One is a working actor, the other is a reformed skater punk, and I grew up loving miniature gaming and history. It was rare for the three of us to all get along for an extended period of time, which is undoubtedly why my parents put up with the incessant claxons and obnoxious, computerized voices from the board game The Omega Virus. It was one of the few things I remember all three of us wanting to play together on a weekend.

On the surface, The Omega Virus is one of those gimmicky, flash in the pan 90s games that are easily relegated to the past. The story of the game and its understanding of technology are the laughable tripe of the pre-internet era. Players are attempting to locate a hostile computer virus that is hiding in a room on a space station so they can blast it. This is making me want to watch Johnny Mnemonic! But the endless variation of gameplay, helped immensely by a surprisingly well designed computer aide, made it a classic in my household.

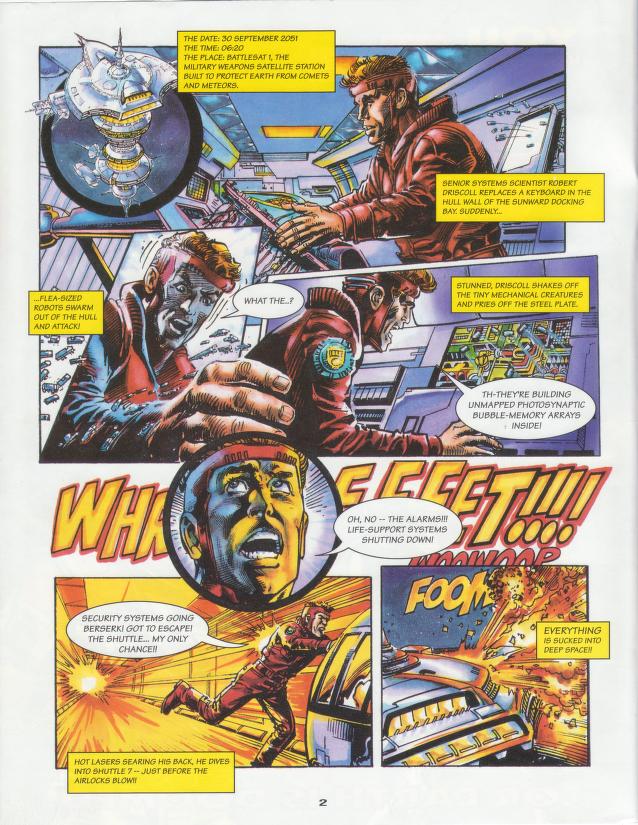

The Omega Virus was released in 1992 as a standalone game. Along with the board and game pieces it came with a cleverly programmed computer which had five buttons (Start, R (Repeat), 1 (Search), 2 and 3) and a speaker, but no screen. All vital aspects of gameplay were conducted through and tracked by the computer. Almost all visual and physical elements of the game were cosmetic and not strictly necessary, though they were very helpful for keeping track of things, since the computer had no screen or readout. The board for TOV was divided into four sectors, each with a flap that contained a rules quick reference and codes for all actions in the game (more on those later). Each sector contained rooms which came in four different colors (green, yellow, blue and red), and each room had a unique, three digit code. Rooms were connected by hallways with spaces for tracking movement, which was the only thing players were responsible for tracking on their own.

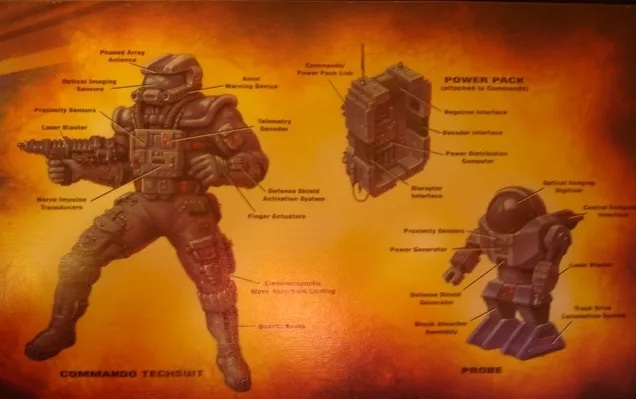

To play a game of TOV players hit the start button and follow the instructions to enter the difficulty level (how much time is put on the game clock), how many people are playing, and then record a secret, two-digit code for each of them. Arranged on the computer console are color coded access cards and plastic bits that will be added on to your commando’s “Power Pack” when they are awarded to you in-game. Players start with the green access card and thus the ability to enter green rooms. The computer tells players who’s turn it is. Players have to move to different rooms and perform a search where they may find: nothing, an ambush, a colored key card, a “probe” (droid), or a piece of equipment. After searching a room the computer will say a code. If your code was said on your turn then that meant you had located the virus, but you cannot attack it until you have all three pieces of specialized equipment: Decoder, Negatron and Disruptor.

Gameplay is frenetic, with a sense of urgency set by two different computerized voices that get increasingly manic as the timer winds down. At any time during the game the station’s computer (we would call it an AI today) pleads for help and the voice of the virus mocks it and the players, calling them “fools” and “human scum.” Sectors will be shut down by the virus as play progresses, decreasing the play area and the number of rooms that can be searched for the necessary items. When players share a space they have the option of ignoring or attacking each other, which can destroy a piece of equipment and send the player back to their starting position.

In keeping with my recent nostalgia kick, I busted out my old copy of this game to play with my kids. I was surprised to realize how straight forward the game truly is, but I can see my boys struggling to juggle all the information it throws at them. I am also struck by how well programmed the console is. To perform any action other than moving (search a room, attack a specific player or droid, attack the virus) players need to enter the appropriate code. The console tracks which access cards each player possesses and will grant or deny access appropriately. It also tracks which pieces of equipment each player has in order for them to get to the end game. It also keeps track of the clock and gives updates (though there is no readout), randomizes the contents of each room and the location of the virus, and tracks whether or not players have located their probe. To be clear, the only information the player ever manually enters during the game is room numbers and attack codes. That’s some pretty impressive coding!

All in all, I really enjoyed teaching my boys to play this game. They love it and can play it together, though the Virus wins at least as much as they do. I won’t be busting it out during a game night with my buddies, but it is shining its role, doing what it did for my parents over thirty years ago: giving my boys a shared experience and giving me back a few moments of my weekend.

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!