Before you toss that d20 down, stop and think: is it morally right of me to change the course of fate by doing this? Do I deserve to roll this die? Ha ha just kidding. Unless…?

What to Die For

Dungeons and Dragons, like most other roleplaying games, uses dice for its resolution mechanic. You roll a die, you add your bonus, you tell the DM what the number is and they tell you if you succeeded. It seems like a pretty easy way to handle things, on the surface.

However, let’s take a look at it on a slightly deeper level. Yes, of course as the DM you can ask for a die roll for anything. And in lots of cases it’s warranted- especially in combat. I’m absolutely not recommending you change that and move over to a game of childhood pretend that just boils down to “I got you!!” vs “No you didn’t!!!!!!”

But outside of combat, there is a lot more discretion to be had in resolving things. Rare indeed is the DM who will call for a roll for everything that you do- no one needs to make an Acrobatics check to walk across the bar to get a drink, or a Charisma check to ask the bartender to pour you another round if you’ve got the coin. These sort of trivial, everyday tasks clearly and obviously don’t need a roll.

But where does one draw the line on that? It’s probably safe to presume that jumping up onto a table to make a dramatic proclamation doesn’t need an Acrobatics roll, either. But how about leaping up to stand on a banister rail? What about jumping over to grab the chandelier? Somewhere along the gradation, the DM is going to want to call for a roll, so how do we draw the line? I would argue that there are two broad ways to make that choice from behind the DM’s screen, and each comes with its own considerations.

The Skills of an Artist

The first broad way to make the choice is driven by versimilitude- that is, giving the game the appearance of being realistic. (Games, by definition, are not simulations of reality, but we can give them varying levels of accuracy to suit our purposes.) So from this perspective, we can look at the character’s capabilities and what they are attempting to do and ask ourselves if they are likely to succeed at the task. This approach is explicitly reinforced by the rulebooks, which note that characters can “take 10” on a roll if there is no particular pressure on them nor consequences to failure.

This is a very useful guideline when dealing with characters of varying skill levels at various tasks- a master archer certainly should be able to shoot the hat off a guard’s head if the man isn’t expecting it (or remains still for the stunt), but a more amateurish combatant might need to roll for it. This also can work as something of a “reward” for players who invest into unusual skill or tool proficiencies- a character who is a leatherworker probably doesn’t need to make any special effort to repair their armor after it gets damaged, but you might ask someone less skilled to do so after they are doused in acid. Do be wary of this, however, because if you always have a proficient character succeed at tasks without rolling it not only makes the game feel less challenging, but also denies the player the opportunity to use the skill they went out of their way to invest into.

The other guideline, and the one I use more often as a DM, is more narrative in scope- ask yourself what the consequences for the roll are. What will happen if the character succeeds? What will happen if they fail? How will this roll change the game?

This sort of thing is especially important when you have the players searching for clues; if there is a hidden note that the players need to find to advance to the next part of the plot, why make them roll for it? You’ve decided the clue is there. You’ve decided the clue is necessary. Have them simply find the clue rather than calling for an endless series of Perception or Investigation checks until someone finally gets the result you want. Is this a contrivance to move the game forward? Yes, absolutely, but all adventures are full of those already, so you shouldn’t feel bad about “allowing” your players to discover a necessary item for the game to continue.

Outside of that context, however, the idea can still be useful. If one of your players says they want to leap onto the giant’s back to try and get at a weak point, before having them roll you should think about what you want the roll to mean. First off, is what they are asking possible? A character with the advantage of high ground or some sort of magic (e.g. Jump) can probably do it, but perhaps others might not be able to. Second, what are the consequences, both positive and negative? Nothing detracts more from a game than when the players roll a die to do something and the DM simply says “nothing happens” or “you waste your turn.”

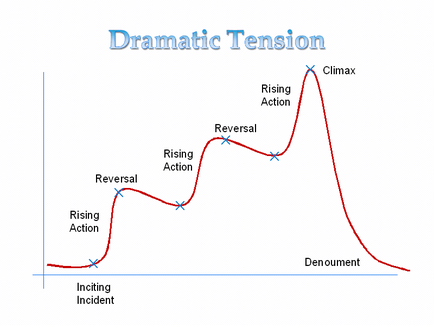

Dice rolls should, ideally, always raise the stakes or create tension. If the player decides to try and leap onto the giant, perhaps you says that a success will allow them a greater chance (or even a guarantee) of critical hits, while a failure lowers their AC or knocks them prone or deals some damage. The key here is that all possibilities on the dice roll result in something interesting happening- this creates tension in the game, and will hopefully arouse the interest of your players during that nail-biting moment while the die is still tumbling. However, as part of this it’s also important that there be some parity of outcomes- a bigger risk should have a bigger reward. It is not fair to your players if you decide that climbing onto the giant’s shoulders will be a DC25 Acrobatics check and give +1 to hit if they succeed but do 35 falling damage if they fail. Similarly, make sure your players understand what the benefits and risks are when they are making the roll- you don’t need to tell them exactly what will happen if they fail, but they should have a reasonable idea what sort of consequences there may be.

Resolution

Dice rolls are how we create the dramatic tension in scenes during a roleplaying game- will the heroes make it to the top of the cliff in time, or will the dragon riders get there first? Can the paladin defeat the evil vampire in hand-to-hand combat, or will they be felled? Can the team sneak past the city guards without being noticed, or will their ruse be uncovered? These moments of drama are what pull viewers in to a television show or story, and in the context of a roleplaying game they perform very much the same function- but rather than leaving their resolution entirely to the convenience of the narrative, we introduce an element of randomness so that the players (who are both the audience and actors for the story) are kept on their toes as much as anyone.

Because of this, we must try to avoid devaluing these moments of tension by pointless rolling of the dice; while not every dice roll should have the fate of the entire campaign hinging on it, we want each one to be a decision point that can send the game in two (or more) different directions. If there is only one way forward, don’t roll the dice for it- just have it happen. And by the same token, if you are going to have someone roll a die, make sure you are prepared with interesting outcomes for both success and failure. Remember as well that “failure” on a check doesn’t necessarily mean that the action doesn’t do what is needed to advance the story, only that it doesn’t happen in the way the players were hoping for. If you are having them make a Wisdom check to search the streets for a contact that can get them important info, a failed roll resulting in them finding nothing will simply drag the game to a halt and force the party to try rolling again. But having that failed roll result in them finding out that the contact was kidnapped gives the players a new goal- they’ve got to rescue their friend! Similarly, a failed roll might also mean that the authorities have been alerted to the PC’s plan and give them less time to converse or force them to deal with a combat encounter before they get the info. Failure should not mean a dead end- it should mean a more difficult path to the end of the story.

Remember, you can get your roleplaying supplies at great discounts every day from the Frontline Gaming store, whether you’re looking for a new set of books or the monsters to craft the perfect encounter.

Another point I would add is this scenario:

The player asks “Can I seduce the lich?” Or “Can I ask the king to abdicate in my favour?” Or “Can I try to steal the armour the knight is wearing without them noticing?” You say it would never work.

They ask if they can roll anyway and get a nat 20…

Do you now suddenly break the immersion and lose the verisimilitude you have created by and say yes, it works or do you squash the excitement of the moment and still say no?

The simple answer is you say no but not then. You say no when they ask to roll. Just like a roll without a reasonable possibility of failure shouldn’t be required, one without a chance of success shouldn’t happen.

Yeah, absolutely. One of my personal pet peeves in gaming is players who like to think that a natural 20 on the dice should be an infinite wish-granting engine that lets them do anything they want; rolling a 20 on Acrobatics doesn’t let you fly, it just lets you jump as well as you’re capable of. Setting the stakes before the roll can help to prevent this, as it lets them know what the expected outcomes will look like.

Which is not to say that you can’t have something exciting happen on that magic twenty, because some players like to play for the long shot. Especially if they have put good roleplaying into it and the action will add to the excitement of the game (as opposed to ending things anticlimactically), it’s perfectly okay to tell them “you can roll but you’re going to need to do very good.” Managing to outwit the Great Wyrm Red Dragon and free your friends from captivity will be a story to tell for years, and that’s what the game is about.

True but I do feel the pain of some players that want to play a skillful character but is too new playing the game to know that magic trump’s all. Even the best rolls are outdone by 0to1 level spells with ease.

So I understand that player would want to push what skills can do because by level 6 and above they understand they will never get to come close to what is now trivial to a spell caster.