Welcome, 40K fans, to a series of articles I am writing about some of the deeper aspects of Warhammer 40,000.

These articles are a thought exercise, and by writing them I hope to improve my thinking about 40K and its fiction (and maybe about much more). Topics in this series will be wide-ranging and will not shy away from moral or philosophical issues that some may consider sensitive or even controversial. I would rather risk the conversation, so while you or I may not agree, I look forward to hearing why. Consider yourself warned for lore spoilers as well. Also, check the Tactics Corner for more great articles on gaming in 40K!

Addicted to Misery

In part 1 of this series, we discussed how good can and does exist in the Warhammer 40K universe. In part 2, we discussed some of the delineations between good and evil in the universe, and attempted to tackle the idea of moral relativism. Today, I am going to poke around with what I consider an affliction that is not unique among fandoms and consumers of fiction – an addiction to misery. This crosses a lot of the same ground as a real-life mental health problem outlined better here, though I’m not speaking of this particular mental health problem as a diagnosis in the community directly.

So, what do I mean when I talk about an addiction to misery? For the purposes of this article, I mean that we as consumers and as an audience are addicted to the idea that there are no good guys, and are addicted so much that we reject any attempts to bring in objective good and heroism to our stories. To break from 40K momentarily, I have heard this articulated by drawing comparisons between fantasy series like The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones. The crux of this argument being that the story in GoT is better than LoTR because the characters are all broken, damaged, and terrible to each other, making them more “real” than Tolkien’s portrayals (which falls flat under any analysis of Tolkien’s characters that is more than perfunctory, and fails to take into account the mythic styles in which many of his stories are told, but I digress…). It is certainly very popular in modern media to have extremely flawed characters undergo a journey while struggling from some mundane or moral affliction, and it’s a key part of the appeal of many anti-hero characters. Even in a comedy series like “Rick and Morty” or “Archer” we are basically reveling in the miserable ways that a group’s collection of dysfunctions bounce off of each other, satirizing themselves and the audience while bathing in nonsense and nihilism.

I definitely respect storytelling that is more than black and white representations of people and circumstances. That said, giving fans of 40K or even fans of “good guys” something good to root for isn’t making the grimdark a black and white moral picture. After all, it doesn’t matter how much white you add to grey, it will never be purely white again, but lighter grays will serve to better contrast the dark ones all the same. If everything is just dark, then an image loses definition, and storytelling works much the same way. Stories grow stale without contrast.

I think that this pseudo-romantic addiction to the worst parts of people and the way we tend to overvalue flaws because of the pretense of “realism” doesn’t really allow readers to properly understand the purpose of flaws in powerful storytelling, or the strength that comes as individuals overcome them. In fact, the most powerful stories in 40K really capitalize on the proper use of flaws, even when the protagonists would easily fall into the villain category, (such as the characters in “First Claw” in the Night Lords series by Aaron Dembski-Bowden). Meanwhile the ones that don’t respect flaws often get labeled with dismissive “bolter porn” epithets shortly before they are lost or overlooked.

Pushback Against Heroism

Much of the genesis of my line of thinking here came from a few sections of an article I saw about the Warhammer community on Vice, which I’ve linked here. The article itself is about alt-right culture wars -which I have no intention of commenting on here – but there are quotes in there that I want to bring out here that illustrate my point about an addiction to misery.

“Thomas Parrott freelanced for Games Workshop until June, writing novels for its Black Library publishing arm. He thinks that adopting a surface-level narrative of “good guys” versus “bad guys” – in a bid to appease the parents of younger customers who might otherwise be put off by 40k’s cartoonishly grim lore – opens the door to a troublingly simplified reading of the game.

“It is really easy to misinterpret the Imperium [of Man] as being presented as a ‘good thing’, as opposed to what it originally was, which was lampooning the very idea of this totalitarian state,” he says.”

Vice Article

We’ve talked about the Imperium as satire of totalitarianism in multiple capacities in several articles in this series. We’ve also talked about good guys and bad guys in 40K’s setting. There’s a plethora of evidence over the last 30 years supporting the idea that the Imperium is such a terrible place to be that even the author of the article above describes it as “cartoonishly grim,” a turn of phrase I find interesting considering how few cartoons outside of Japan could aspire to be called grim. Follow that commentary up with this quote by Leakycheese from the same article:

“Some changes to the lore of 40k would not go amiss, either it… should be abundantly clear that the Imperium of Man aren’t the “good guys”… “They need to put the satire back into it,” he [Leakycheese] says. “The other thing they need to do is stop making Space Marines appear as heroes…”

Vice article

With the nearly absurd amount of justification for a dark reading of the Imperium, why would there be a concern that 40K was changing to something more hopeful? Look no further than the greatest catalyst for change in the Imperium since the Emperor himself: Roboute Guilliman.

Daring to Not Be Miserable

40K’s narrative remained at a minutes-to-midnight doomsday clock for years. Many among the community, myself included, never expected the clock to move forward. This is especially true considering that there were tens of thousands of years to explore in the fictional timeline. The Horus Heresy series, which had been the primary lore focus for many years, was a setting almost as popular as the main one. Then we were surprised to learn of the revival of Roboute Guilliman, and the change that he brought with him. Moving the clock forward with hope was to the fans much like standing on a train braced for it to slow down only for it to jerkily pick up speed, sending you completely off balance.

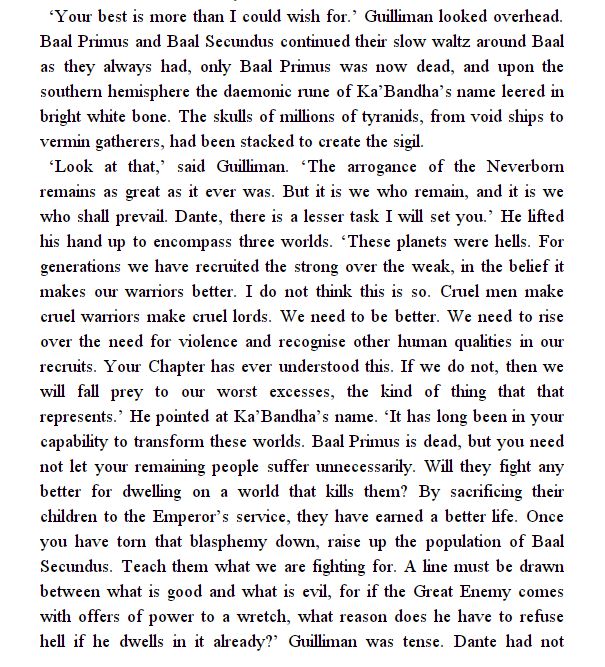

I imagine that’s where a lot of the unrest that comes with the newer direction of 40K comes from. Here’s an excellent example from the Devastation of Baal novel by Guy Haley.

So here we have someone in 40K daring to say that the Imperium can grow and be better than what it is. The idea that the Imperium has a journey now and that it can develop into a better place to live has its genesis. Maybe, just maybe, it doesn’t have to always be grimdark for humanity.

Boldly Growing

To many in our community, this is unadulterated heresy. 40K, after all, was supposedly built as a joke on fascism, religion, and totalitarianism. How dare that concept evolve! How dare the concept mature! How dare it change! How dare it attempt to take itself more seriously than its origins! Of course, in that same breath, varied groups of people complaining over the change will demand that 40K incorporate their particular political branding and ideologies. This becomes the crux of the problem that forced the clock forward, in that 40K cannot adapt to include or represent whatever it is that it should or should not accept (depending on who you ask) without first allowing the setting to permit those kinds of attitudes and behaviors in the first place, or doubling down on the things that made it a regressive, depressing parody in the first place. To put it simply, it can’t change while staying the same.

This is where a lot of the critiques leveled at 40K and its setting in the Vice article really start to contradict themselves. The critics demand that GW create new opportunities for acceptance by a wider audience but also says “don’t you dare disregard the awfulness of the setting or allow your protagonists to be ‘good’ or ‘heroic.'” This puts Games Workshop in a fairly comedic position. Integrate XYZ groups so we can… villainize them? Misery is, after all, fairly egalitarian in the 40K universe already. What the critics of 40K’s changes in setting often fail to recognize in addition to the slight paradigm shift in the Imperium’s moral direction is exactly how much more catastrophic the universe it exists in has gotten.

Of course none of this has even begun to address what 40K’s grimdark setting took away from its storytelling potential, and what the possibility of an Imperium that can grow into something better can do for both the residents and readers of the universe alike. Is the sacrifice of 40K’s awfulness such a great loss that it can’t be eclipsed by the benefits of giving the totalitarian regime at the center of its narrative an opportunity for moral growth? Is a painting better off when viewed without contrast or color?

Aiming at Something Better

If we were to take a very surface-level stab at what the Imperium was meant to be in the lore, then fundamentally the Imperium was meant to be the vehicle that the Emperor could use to carry mankind to the next stage of human evolution, thus freeing the species from the predations of Chaos. We’ve already discussed the catastrophic failure that was, and how the absence of his guidance evolved his secular totalitarianism into a declining superstitious totalitarian state. Now, of course, we have Guilliman at the head of the great Imperial machine. Guilliman is a man of incredible competencies mentally, administratively, physically, politically, and more. Beyond that, he has a vision to not just coast on the status quo, but to grow and change the Imperium and make it a better place to live. He’s developing and sponsoring the development of new technologies, instituting change on all levels of the Imperial bureaucracy, and is even making changes to the vaunted Codex Astartes. Let’s get it out of the way right now that all of his methods are not completely good (whatever that really means), but at the very least are better than the methods that have been used by the Imperium for a long time.

From a storytelling perspective, this is an absolute goldmine of opportunity. Not only must Guilliman contend with the greatest calamity to hit mankind since the Horus Heresy, he also has to fight those within the old regime who resist the changes he’s trying to implement. The potential for conflict between him and the ecclesiarchy alone could spawn its own lengthy series. This is engaging storytelling rife with opportunities for conflict, and Guilliman’s ambition for a better Imperium is barely even nascent at this point – contending at its very genesis with the millenia-long momentum of a catastrophically tyrannical regime on the verge of overthrow by it’s long-ignored sins, ennui, ancient evils, and the apocalyptic embodiment of nature itself. And this setting is too… hopeful? Fellow fans and hobbyists, I must present the possibility that perhaps we are made parodies by our own fandom if we can look at the current state of 40K and the Imperium to perceive it as too optimistic. Beyond that, can we even imagine the kind of unreadably drollish mess of a story it would be if 40K was simply a catalog of the newly-awakened primarch’s descent into disillusionment? Is having “good guys” really such an unforgivable sin?

I believe that this is where Guilliman’s narrative in the modern 40K fiction, and therefore the Imperium’s own direction, opens up more possibilities for meaningful storytelling. The Horus Heresy series, after all, wasn’t successful because it was a dry historical account of a fictional future war. It succeeded and resonated with readers because it had heroes who struggled against darkness – a darkness we knew they would not be fully prepared to resist – and it created a vision of an ideal. Inasmuch as that ideal has not been fulfilled, the Imperium has been judged by it ever since. This is a philosophical principle for growth and development – your ideals judge you. This means that every second that the Imperium isn’t improving, Guilliman is failing. It raises the stakes. It’s compelling. The fact that we don’t know the ending means that we need a character to follow, and what is so wrong with it being a better version of mankind?

Forgiving Mankind

The theme that 40K’s protagonists – the Imperium- were caricatured as just a different flavor of evil than, say, Chaos or the Dark Eldar has lost its narrative flavor. This dead horse has been beaten to its constituent atoms, which were then violently split to form the comically common exterminatus edicts dashed like salt and pepper across the Imperium’s history. Inasmuch as 40K were to remain at it’s minutes-to-midnight clock setting, stories that wallowed in the excessively caricatured depravity could still function. During that time, as if in contest with itself, 40K tried to up the ante constantly on what awful things you could expect people do to each other with each new story. The Imperium in Warhammer 40K is guilty of the most profound sins that the authors could come up with. Narratively, the Imperium’s sins stagnated the universe and degraded the setting, much like the Golden Throne losing its potency. Even still, the idea of progression doesn’t abandon the old themes or act as if it never happened. Instead, it makes the dark themes of the Imperium’s past a springboard for growth – and considering the hole that it has been in, the Imperium needs all the help it can get to get out. And heaven forbid that as a side-effect we actually provide better contrast for our villains.

If the Imperium were a person, it would be an amalgamation of every deplorable human trait wrapped into a miserable being dying of cancer, and we would never stop picking at the scabs or letting the person forget exactly how awful they are or how close they are to death. Then, in its darkest hour comes Guilliman. Guilliman comes with redemption of a sort for this person. Not the absolution of a Christian salvation, but just the promise of improvement. Maybe it starts with a shower, maybe it starts with Guilliman just pointing the person at a shower. Maybe, like all improvement stories, the person takes a few steps towards the shower then takes a few steps back, resisting change, before continuing again. Do we then, as fans, step up and demand that the Imperium go back to where it was? Are we so determined to pick at its scabs that we don’t even want to see if it could get better? Do we pretend that the journey of this damaged, awful thing is better when we get to watch it die without the possibility of redemption or recovery? Must it stay bad? What does that say about us?

This is where I feel the critiques in the article cited above fall flat. They do not allow the Imperium to be more than the satire it was, or maybe someone will interpret it the wrong way. The resistance to growth says things to old and new fans alike: Do not allow the protagonists to be “good guys,” because humanity must remain irredeemable. Don’t risk Astartes being heroes, because they could be commandeered as a symbol for something bad. Do not forgive mankind. Do not allow those new people who we hope to bring into the setting a chance to connect or relate to something resembling a journey towards a positive outcome. Be accepting and open, but do not allow the conditions for acceptance and openness to happen in the lore. Do not permit the setting to dare to be better than the worst thing it did, or grow beyond the worst version of itself, but also be inclusive. Don’t add more color or more contrast to our shades of grey, or we will no longer be able to satisfy our addiction to misery.

An Ongoing Conversation

Thanks for coming along with me here. Do you think that 40K should never stray from its grimdark origins, or do you see the potential for growth as an exciting opportunity for change? Are you somewhere in the middle? Let me know what you think.

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!

Posted on August 10, 2020 by Chris Morgan in 40K, Blood Angels, Editorial, Review { Edit }

I love this series, keep them coming!

I agree that it’s time for all of us to rethink the 40K lore. As you said, when the setting was created it was purposefully lighthearted in it’s portrayal of the evil of the Imperium of Man. But 30 years of lore have really fleshed out the background, and while the writers attempted to maintain that level of parody, it has actually swung into the realm of the absurd, with each writer attempting to outdo the last in showcasing the inhumanity of the Imperium of Man.

I don’t read much of the novels anymore, but that passage you quoted and the thoughts that followed actually have me excited that GW might be moving the story in that direction, with the Heresy series showcasing the high hopes of the Emperor, quickly dashed by a fall from grace, 10K years of stagnation, and now in the third act, a new hope for redemption. It really opens up the range of stories that can be told, and empowers the hobby to have a real storytelling voice. Parody and satire are great, but it gets old so fast.

A few disjointed(maybe not) points:

1) There’s an adage that given sufficient time, an anti-war film will be repurposed into a pro-war one…usually by soldiers or the lay audience. Maybe not “pro-war” per se but certainly reveling in depicted martial violence. Full Metal Jacket is probably the best example of this. Warhammer’s now decades of parodying Thatcher era Britain followed the same course. It had a message but not a mission. That irony isn’t coming back unless they style a Warboss after an iconic politician.

2) Postmodernism is characterized by the death of grand narratives. Warhammer 40K *was* postmodern because it was a setting, a sandbox, for men (or xenos) walking in the footsteps of giants. There’s a certain awe in the wreckage of Ozymandias’ empire. No narratives, no historical missions, just the pure assertion of competing factions.

Imposing a central storyline unto a previously decentralized setting, I think, is the source for much of this angst surrounding our beloved toy soldier franchise.

What was once a sandbox for creatives is quickly becoming a slide – “play” (development) occurs in one direction now. This being led by a Primarch (who is also a stand in for GW & modern audiences), one of the giants of old returned. Sort of kills the wonder. Very difficult to un-postmodern something.

3) I haven’t read much of the Horus Heresy, but being in the past, it’s story enriches the 40K setting as a setting.

4) Warhammer stopped being weird, or started hiding its weirdness, and that objectively sucks. Ian Watson’s “Space Marine” reveled in how effing weird it is to be a child-soldier implanted with extra organs and sent to kill aliens and humans across the galaxy with your bro-rivals. Older art styles left things fuzzier/less defined and allowed us to fill in the gaps. Weirdness is of course slain by familiarity, but the new direction feels more conventional.

5) As a solution, my humble opinion from a writing perspective is spend more time developing tertiary factions while still leaving room for imagination. Eldar have a lot of room to be weird, wild, and compelling. What are Exodites up to? Don’t write a novel about how their economies work but give us something to chew on. Do this enough and you’ve got a basis for model sales,too.

Anyway, thanks for the series so far. It’s been great to see constructive engagement with the writing meta that isn’t just reducing Warhammer to “problematic” or “X Y or Z needs to change or I’m done!”

Excellent response. Thanks for taking the time to comment!

I can’t comment too much on Thatcher, as I’m neither part of the UK or researched enough on the topic, but I often hear about how Thatcher “inspired” 40K.

I think that #2 really illustrates the weakness of the postmodern way of thinking. It should be unsurprising then that the more they embrace grand narratives, the greater the setting has become (and their sales). Meaningless things offer little value to consumers. I won’t hide that I don’t find a lot of value in postmodernism.

#3 is correct. A tragic grand narrative for sure.

#4 is an interesting perspective. There is still plenty of mystery in the 40K universe, but I understand your desire to be able to fill in the gaps yourself. I think 40K still lets you do that – the sandbox is still there even if the weirdness (as you describe it) is perhaps a little less present.

So far as #5 goes, fair point. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with developing other factions. I will say that I think it will still be difficult to try to develop these factions from any other perspective than human. Xenos they are, but I think you run into #4’s problem even more by explaining an alien’s weirdness in human terms – since that’s all we can understand. We are humans, the characters in alien fiction are written by humans, and we can only understand them as humans. This is where the Horus Heresy has gotten things really right in that they never write from the Emperor’s perspective. He remains unknowable. If you want to keep the weirdness, it might be best to do that for most of the alien races as well.

Thanks for the conversation!

Has GoT been completed as a series of novels ? Does it count as quality literature when compared to LotR ? Did the televised GoT rather not just pander to the nature of those who watched it for the sex and violence (HBO did the same to “the Tudors”)?

40K fits the pattern of the Roman Empire, Holy Roman Empire and many kings of England/France/Spain. When an absent King many miles away pulls the strings and any divergency is seen as evil. After all, 40K is written from an English point of view in London, Newark and now Nottingham. It’s hard to walk around Nottingham without a statue of Robin Hood springing into view – fighting against the evil Prince John, whilst King Richard is crusading many thousands of miles away. Newark had a famous battle where King Charles I was defeated and executed in London. The serfs and peasants of feudal England had miserable lives, often dying in childhood and normally 25 was seen as old age.

It’s impressive how much wrongness is in your post.

Let’s start by the most obvious, glaring one that is my personal pet peeve : 25 years wasn’t old age at the time. 45 was. While a lot of infant died (and that’s why the average age of death was old), once you were 10 or so year, you would often live to 45, 50, or 60 years.

The rest is more complicated to explain and somewhat more subjective, but, really, if you think that feudal english peasants died at 25 years, please educate yourself. It’s one of the most embarassing mistake together with thinking all thoses peasants were white.

Look you can’t just come in here with your “facts” and “knowledge” and shoot down all of the wild superstitions and assumptions that Rob is making! How dare you, sir! HOW DARE YOU!!!

I would argue on LotR being the standard of quality literature for fantasy. The first book is great, but the second one is a complete slog to try and get through. Plus, GoT was a great show and not really pandering. It didn’t manage to stick the ending great, but it was still a solid show throughout most of the run.

Also Rob, you forgot to mention someone who works for GW or ask random non-sequitur questions in your comment. Please go and correct this, we have standards of trolling we are trying to uphold here!