Welcome, 40K fans, to a series of articles I am writing about some of the deeper aspects of Warhammer 40,000.

These articles are a thought exercise, and by writing them I hope to improve my thinking about 40K and its fiction (and maybe about much more). Topics in this series will be wide-ranging and will not shy away from moral or philosophical issues that some may consider sensitive or even controversial. I would rather risk the conversation, so while you or I may not agree, I look forward to hearing why. Consider yourself warned for lore spoilers as well. Also, check the Tactics Corner for more great articles on gaming in 40K!

I’ve also added my first narrated version of this article up on YouTube. If listening is easier than reading for you, feel free to check this out. I’ve done some quotes and visuals on here as well. I’m very new to the video making business, but this was a great opportunity to learn.

An Introduction to Eldar Mythology and Its Connections to Our Own

Many cultures have asked questions about the origins of life and the world we occupy. Our history has a wide variety of creation and origin stories. Legends like Marduk in his clash against Tiamat the great dragon of chaos from Mesopotamian myth, the formation of Midgard from the body of a dead giant in Norse mythology, the creation of the world from a great sea at the rising of the sun as depicted in Egyptian mythology, as well as the commonly known account from the Old Testament of the Abrahamic religions. Many of these stories borrow from each other in many different ways as they have influenced each other across history, and many of their themes have made their way into the creation mythology of 40K.

I should make note here that I’m not trying to make a case that 40K origin stories are just carbon copies of old myths, but instead I am saying that the themes of old myths and stories have undoubtedly influenced these works. Consequently, the morals and themes derived from the Eldar mythology will resonate with those they are rooted in. Far from being simple easter eggs, these tie-ins resonate with readers, as do the themes. The connections between these narratives offer greater symbolic meaning when analyzed side-by-side.

As an example of this, the Eldar have a full pantheon of gods that nod to many different aspects of mythology from history. This pantheon touches on many of the traditional themes common among pantheons we are familiar with, such as having a ruling god (Asuryan) like Odin, Ra, or Zeus who presides over the pantheon. At odds with this order is Khaine, a god of war or murder often in conflict with the other gods and mortals, much like Hades, Ares, and Set. There’s also a goddess of the harvest, life, and healing named Isha, like Freya, Isis, Isha, and Hera to a lesser extent. Heg, goddess of fate, was part of a trinity of goddesses that resembles the three crone seers of Greek mythology. A trickster god, Cegorach, is much like Loki or Hermes, who seek to get the better of their peers and set them against each other for their own satisfaction or to pursue their own designs. Each god in the Eldar pantheon has their mythic cycles, with tales of war and symbolic allegory that impact how the Eldar speak and interact with each other. Even the Exodites, considered the most primitive (or perhaps most rural) of the Eldar have a pantheon of animal gods much like tribal societies past and present.

Every part of Eldar life is rich with symbolism built into both their body and spoken languages, each being rich in metaphor. Every Eldar must be steeped in the legends of their gods if they even hope to communicate with each other, and it is often this reason that is given for why humans can very rarely speak the Eldar language fluently. This makes the symbolism that constitutes their origins very interesting and impactful, and is somewhat a deviation (and likely deliberately so) from the often clinical or scientific approach to the formation of the galaxy common among the stories in the Imperium.

It should surprise us very little, then, that the main themes of the Eldar pantheon touch on many of the same points and teach many of the same lessons our own myths do. Many of the Eldar’s specific mythological tales are unknown to us as an audience simply because they have not been written in more than vague terms or hints in codexes or short stories. Some tales, such as the War in Heaven and the Fall of the Eldar are much more easily relatable to stories from history such as the Fall of Man from Genesis in the Old Testament, and the story of Cain and Abel from that same book. I am focusing on these connections for this reason, but I wanted to make sure to give some attention to how many of our own mythological stories show up in the lore of the Eldar.

The Fall of the Eldar

The Eldar fall is probably the single-most important lore event in Warhammer 40K outside from the Horus Heresy, and certainly the most influential Xenos lore in terms of impact on the galaxy. I touched on the Fall of the Eldar and the War in Heaven in my articles on both the Aeldari and Necrons, but I will summarize the key points here.

With the Necrons seemingly defeated after their long and terrible war, the Eldar race languished in victory. Created by the Old Ones before their death at the hands of the C’tan and their Necron slaves, the Eldar are flawed because of the rushed nature of their creation. The Old Ones gave them an incredible psychic potency as a means of fighting the soulless Necrons, and its intensity meant that the Eldar have a depth of emotion and experience that exceeds that of other races. To the Warp, which is a collection and a reflection of the emotional and spiritual state of the galaxy, this means that the Eldar had and have an incredible influence on that realm. Apparent victory against the Necrons set the Eldar free to pursue their own interests, much to the detriment of the galaxy.

To put it simply, without challenge, the desires of the Eldar turned inward. They sought to satisfy their desires and whims without discipline among each other and across the stars. They set no limits to the depths that their depravity could reach, and set upon themselves with wild abandon seeking new sensation. The Eldar life and death cycle was a cycle of reincarnation, where a spirit would pass into a new body after death. In a society made of reincarnated spirits, it is easy to consider how a reincarnated soul lost to depravity would create a positive feedback loop of horrors as it lived and relived its own lack of satisfaction, and sought new ways to make life interesting.

In the warp, the echo of the Eldar race’s many horrors birthed a new chaos god, Slaanesh, who murdered or subdued nearly the entire Eldar pantheon. Slaanesh is made of the excesses of the Eldar and has taken excess as its domain. The consequences of Slaanesh’s arrival would change the galaxy forever, as the depravity of the Eldar would seduce and torment every living race of the galaxy from that time on. The real-world symbolism of this concept is too tantalizing for me to pass over. Do we as individuals mirror the self-destructive tendencies of our real and imagined societies? Yes. That’s what makes them interesting and relatable, and our consideration of these narratives has value even if the events themselves may be fictional.

Let me be clear in expressing that I’m not saying that this is the only way to interpret any of these narratives, but I am instead trying to derive something useful and meaningful from these narratives as something for us to consider.

The Psychology of the Fall of the Eldar, and the Fall of Man

“The Fall” as an idea existed long before the Eldar. In the Christian tradition, the Fall refers to the fall from grace when Adam and Eve were cast out from the garden of Eden – a paradise of peace, safety, innocence, and plenty. By taking the forbidden fruit, Adam and Eve had disobeyed God and were exiled from their appointed paradise to live as fallen beings who could no longer dwell in the presence of God, and they were now required to toil for their sustenance. As the story goes, among their first children were Khaine… oops, Cain and Abel (we’ll touch on that more in a bit).

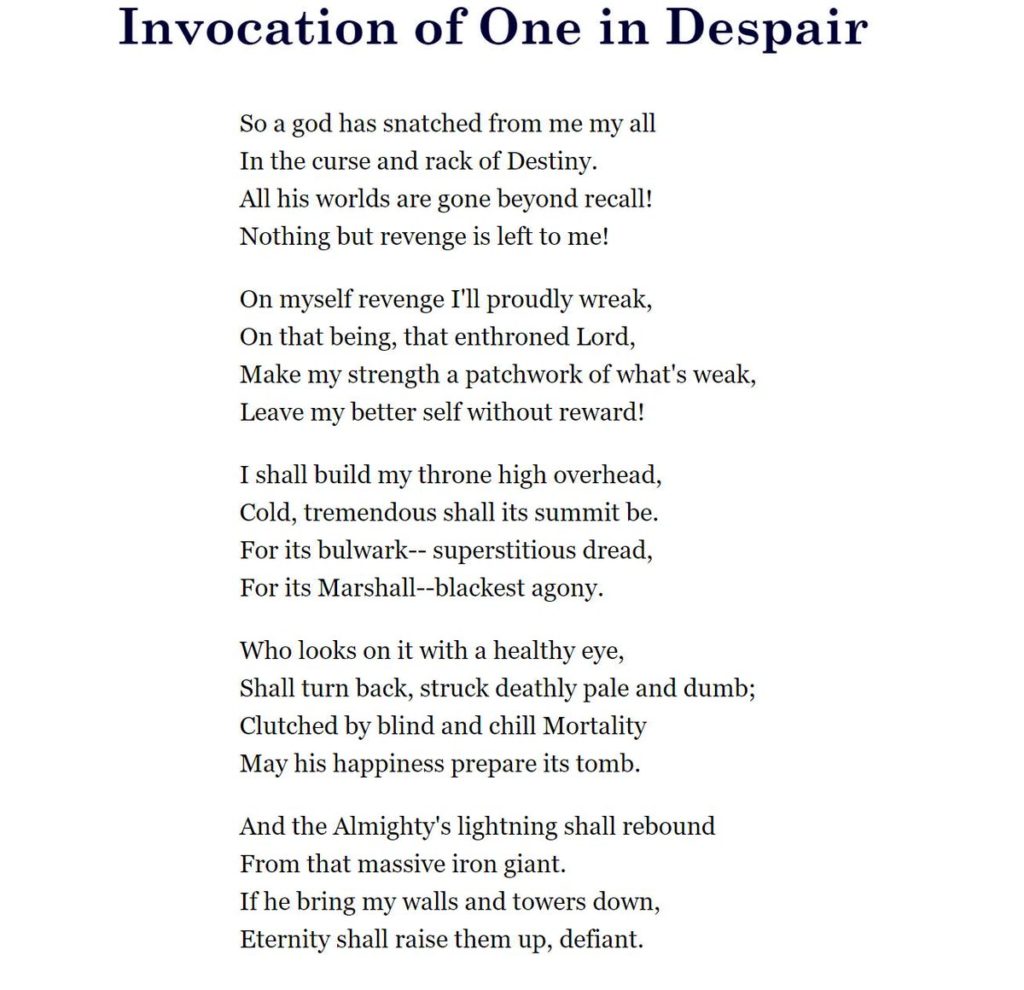

The Eldar story borrows somewhat from the idea of the Fall of Man though not like a carbon copy. The Eldar had purpose in their war against the Necrontyr-turned-Necrons, but when that purpose was satisfied, the Galaxy became their Eden. Without purpose and in a state of paradise, they grew bored. Life was cheap. Existence was without meaning beyond what they made for themselves. This brings to mind a favorite quote of mine from Dostoevsky.

Such was the truth with the Eldar. They had lost their purpose, and turned inwards in a spiral of self destruction that dragged their race from its prime into a shadow of its former self desperately trying to slow or stave off its final death with failing strength. This is part of the lesson in the Fall of the Eldar narrative. By embracing a mode of being that exists purely for the sake of your own satisfaction and by drawing no moral boundaries around the actions of yourself and society, you create a demon that will destroy you. Much like the Eldar, the lesson can come too late, and just trying to be while the doom promised by that demon hangs over you means that you have to work even harder just to keep ahead of it. This is the solution that the Craftworld Eldar (or the Asuryani) find. The discipline and focus that they have to maintain dominates their lives, and always Slaanesh looms in the background with the promise of destruction much like how alcohol looms in the background thoughts of a recovering alcoholic.

A Note on the Drukhari

It is important at this time to point out the differences in coping with the fall demonstrated by the Asuryani and the Drukhari. The Drukhari take a different path, a path that could be very easily likened to an addict. The Drukhari share their suffering with those around them, and everything in their lives becomes structured around the need to feed that addiction. Even in a universe as brutal as Warhammer 40K, being caught in the clutches of the Drukhari is often a contender for the worst fate a person could imagine. They are the end result of a nihilistic attitude and psychopathy. They have gone from living cruelly solely to pleasure themselves to living cruelly just to live. It represents a very real pattern of behavior that can come to people without purpose. One of the closest real-world comparisons I can make to the Drukhari approach to existence is the Columbine killers. I have included this excerpt from an article regarding their behavior here, and I don’t think that I am the only one who can see the connection between the mindset of these very real people and the fictional horror dimension that the Druhkari occupy.

“Because psychopaths are guided by such a different thought process than non-psychopathic humans, we tend to find their behavior inexplicable. But they’re actually much easier to predict than the rest of us once you understand them. Psychopaths follow much stricter behavior patterns than the rest of us because they are unfettered by conscience, living solely for their own aggrandizement.

None of his victims means anything to the psychopath. He recognizes other people only as means to obtain what he desires. Not only does he feel no guilt for destroying their lives, he doesn’t grasp what they feel. The truly hard-core psychopath doesn’t quite comprehend emotions like love or hate or fear, because he has never experienced them directly…

Dave Cullen – The Depressive and the Psychopath, 2004

…’Because of their inability to appreciate the feelings of others, some psychopaths are capable of behavior that normal people find not only horrific but baffling,” Hare [a clinical psychologist] writes. “For example, they can torture and mutilate their victims with about the same sense of concern that we feel when we carve a turkey for Thanksgiving dinner.’“

So, if you were about to make an argument that the Drukhari are surviving just fine after the fall with very little adverse effect and use that as a justification for 40K supporting nihilism as a worldview, then I would say that perhaps you don’t understand their way of life enough to consider it as “just fine.” I think you would have a hard time justifying how that is an acceptable mode of being to anyone who isn’t a psychopath. I feel comfortable asserting that being consigned to that sort of existence is an example of a fall, if not a metaphor of how hell isn’t just a place that you go when you die, and that you can create one while living given enough time and effort.

Applications of the Fall Narrative

So, while there are some differences, the stories of the fall share many of the same themes. You have a group that falls from a state of grace and loses access to paradise. They are left in an uncaring world, are separated from the divine, and are doomed to suffer and struggle until the final days. The Adam and Eve story asks questions about committing sin, and where you may or may not believe in a divine being, as a person it is easy to relate to knowing not to do something bad or wrong (whether culturally or personally) and doing it anyway, and how there are certain mistakes that a person can make that have life-changing consequences. There are things that a person can do that there is no coming back from. Anyone like myself who has watched someone struggle with addiction in ways that robbed them of their potential can easily relate to the story of the fall of man, regardless of whether it was literal history or not. In the same way, the Fall of the Eldar speaks to that on a societal scale in that a society without boundaries given to excess will create the demon of its own destruction.

A Note on the Flood

Noah’s ark is another biblical story that has possible relevance to the fall of the Eldar narrative, but upon closer examination, it didn’t match up very well to me. While a comparison could be made between Slaanesh’s arrival and the divine punishment that was meant to cleanse the world of sin by water, that is where the similarities end. Slaanesh was created from sin, and consumed the sinners with the power born from their own vileness and continued to promulgate its evil on the galaxy after their death. The flood was meant to cleanse the world and give it a fresh start. While the craftworlds could be considered arks like Noah’s, the survival of Commorragh (a homonym for Gomorrah, a den of iniquity from the Old Testament) somewhat cheapens whatever cleansing effect Slaanesh’s “flood” would have had. As such, while some connection can certainly be drawn, it doesn’t work well enough as an analogue for me to spend a lot of time putting together.

Khaine and Cain

Although only a short series of paragraphs in the Old Testament, the story of Cain is nonetheless packed with symbolic significance that has valid tie-ins with the story of the fall of the Eldar. Cain and Abel, two brothers, are commanded to bring sacrifices to God. Cain’s sacrifice is rejected, and he grows bitter over how much better his brother Abel is doing. Possessed by jealousy, resentment, and nihilism, Cain murders his brother in cold blood. Abel’s blood cries out to God from the earth for vengeance, causing God to seek answers from a sulking Cain. This is the first act of its kind among the children of Adam, and Cain is cast out and cursed because of his actions. This is significant for many reasons within the Abrahamic religions, but it ties into the Eldar myth in interesting ways as well.

Khaine seeks to kill the Eldar race (the children of Isha) after learning that they will be the reason for his destruction. This causes a war among the gods, also called “The War in Heaven” (though distinct from the Eldar war against the Necrons). The Eldar, who used to be able to dwell among the gods, are separated from them by the decree of Asuryan and now live in the mortal dimension. This mirrors the fall of man somewhat, in that Adam and Eve are no longer able to dwell in the presence of god, and that there was a war in heaven where the devil and those who sided with him were cast out before Eden was made. The War in Heaven in the Eldar myth ends after Khaine kills Eldanesh, the greatest Eldar champion and a mighty hero, in a duel. As a mark for this deed, Khaine’s hands drip blood from that time forward, giving him the name of Khaine the Bloody-Handed, a god of Murder. This is interesting, as Isha is the goddess of earth and the harvest, and the blood on Khaine’s hands mirrors somewhat the biblical story of the blood of Abel crying out from the earth marking Cain for vengeance. The prophecy of Khaine’s destruction would eventually come to pass, as Slaanesh would kill Khaine and scatter him to pieces during the Fall. Much like Cain, Khaine’s downfall wasn’t a true death, as his lesser incarnations still exist.

The murders of Khaine and Cain don’t mirror each other perfectly, but they share some themes. The biblical story of Cain is centered around sacrifice. Cain was dissatisfied because his sacrifice was rejected. The Bible doesn’t explicitly state why it was rejected, but we know that in many traditions the act of animal sacrifice was considered more meaningful because it was of a greater value than the plant offerings that Cain had brought. In a modern context, sacrifice is an act of negotiating with the future in that denying ourselves of something we want, we exchange it for prosperity in the future. We also know from the passage that Cain nurtured his feelings of anger and bitterness. Psychologically speaking, people in the real world who live and wallow in their resentment produce disastrous outcomes for themselves and for others, as evidenced by many acts of murder-suicide, mass murder, and genocides. Cain and Khaine exhibit this tendency, though on different scales and for motives that are somewhat different. Cain was the murderer of his brother, while Khaine sought to murder the Eldar, and they pantomime human psychology with their motives and actions.

We can, of course, extrapolate a moral of Cain’s story in human society as an object lesson to mean that the value of what we give up (or sacrifice) to god (the future/existence) can’t be done incorrectly or in a halfway fashion if we expect to get the best outcome. Additionally, responding to failure with nihilism, bitterness, and vengeance after our halfhearted efforts fail leads us to hatred for others, particularly those who seem to have it better off than we do. After all, someone like Abel is easy to hate, because he succeeded where Cain failed, and he was blessed for it. In this sense, Cain created the circumstances that led to his downfall by not giving proper sacrifice, by dwelling in his feelings of hatred and envy, and killing his brother. This is telling for another reason, because being blessed and having his sacrifice accepted didn’t entitle Abel to immunity from the consequences of Cain’s hatred – the lesson there being that you can still make the proper sacrifices and be favored by reality/God/your circumstances and then lose all of it because of others’ inability to negotiate properly with reality, or cope with the consequences. Could Cain have bettered his circumstances by resetting himself and making the proper sacrifices? How much worse did Cain’s life get after he acted out the resentment he nurtured in his heart? How often do we as individuals fall into this pattern and find only grief?

For Khaine’s part, he created the circumstances of his own fall as well. By instigating the War in Heaven, Khaine separated the gods from the Eldar both physically and spiritually. Cut off from the guidance of their gods, the Eldar destroyed themselves and the gods with the birth of Slaanesh. Khaine’s hatred and desire to kill the Eldar didn’t come from anything they had done, but came over what he supposed they would do. His motives were purely self-serving, and he justified what he did in the name of survival. Additionally, Eldanesh was killed by Khaine despite being the ideal hero, much like Abel was considered good and blessed by God. This murder marked Khaine as surely as Cain was marked. Had Khaine not acted in such a manner, could the Fall of the Eldar have been avoided? Would the guidance of Asuryan and the other gods have provided meaning and direction for the Eldar in such a way that would have prevented the downfall of their race and the birth of one of the four prime Chaos gods? If we apply this to ourselves, do we often create the circumstances of our own fall by trying to prevent it in the wrong ways? Do we attack the wrong thing to avoid an undesired outcome but instead steer ourselves towards that outcome under another guise?

An Ongoing Conversation

I hope you enjoyed this little foray into Xenos lore and human psychology. It was a bit of a divergence from my usual focus on mankind’s journey in the grimdark. What connections to Eldar lore do you see or are the most interested in? Let me know in the comments!

If you found this interesting, please check out my page Captain Morgan’s Librarius. This is the space where I test these ideas in their first drafts, and also talk about all the other parts of the hobby that I enjoy from painting, community, and gaming to all the rest. It’s also the best place to converse with me about this and many other topics in 40K. Likes and shares are appreciated. I hope you enjoyed this week’s read, and I’ll see you again next time!

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!

Lileath, Isha, and Morai-heg are inspired by the Celtic Morrighan (maiden, mother, and crone).

Excellent connection! I need to read up more on Celtic mythology. I only know a little.

Just for info; he majority of the eldar lore and names are based on Celtic mythologies. Biel-tan? Saim-hann?