Welcome, 40K fans, to a series of articles I am writing about some of the deeper aspects of Warhammer 40,000.

These articles are a thought exercise, and by writing them I hope to improve my thinking about 40K and its fiction (and maybe about much more). Topics in this series will be wide-ranging and will not shy away from moral or philosophical issues that some may consider sensitive or even controversial. I would rather risk the conversation, so while you or I may not agree, I look forward to hearing why. Consider yourself warned for lore spoilers as well. Also, check the Tactics Corner for more great articles on gaming in 40K!

Man, Myths, and Legends

As a student of mythology, the name Horus reminds me of the ancient tales of the mythical being from Egyptian mythology. As a student of philosophy, I see the myth of Horus and look at the narrative for themes and meaning applicable to humanity and morality. As a fan of Warhammer 40K, I hear the name of Horus and see a character very far divorced from those ancient roots. In this article, I plan to look at the myths, themes, and stories of the old Egyptian myths and see how they fit into the ongoing narrative of the Horus Heresy.

I want to make a quick disclaimer here about mythology. Like a telephone game, mythology changes over time and with the telling. It would be impossible to put every version of the Horus myth in the article, but if you are interested in learning more about it then I recommend checking out some of the materials presented in the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum (available for free on their website), as well as academic journals available through the Oxford Press.

Of course, there isn’t just one mythology embedding itself into the lore of 40K either. Abbaddon, for example, is a name from the Bible in the book of Revelation – a name synonymous with destruction and the apocalypse. Molech (referenced below) was a god whose worship demanded the sacrifice of children. Deathfire is a retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey in the Warhammer setting. There are more symbols, mythologies, and legends tied into the lore of this game than I could easily list here or dissect. Today’s foray into mythology will focus mostly on Horus the myth vs. Horus Lupercal ( the name Lupercal, of course, being derived from an ancient mediterranean goddess of revelry).

Horus in the Myths

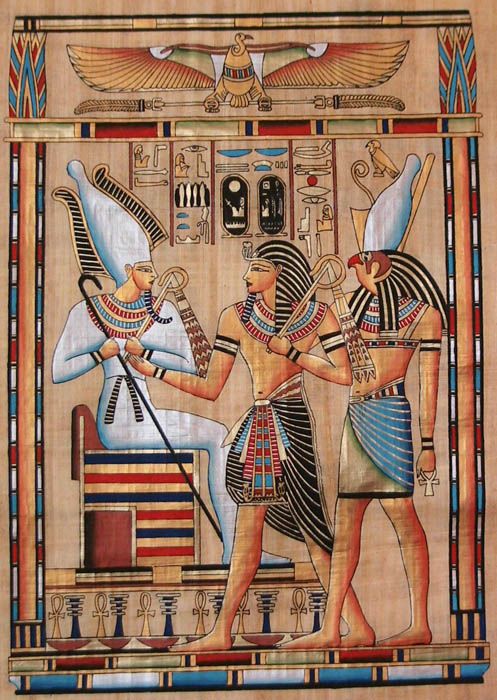

In ancient mythology, Osiris was King of the gods. His jealous brother, Set, murdered his brother and divided his body into several pieces across the upper and lower portions of the Kingdom of Egypt. Isis, Osiris’ wife, took it upon herself to gather the pieces of Osiris to attempt to restore the King. Taking the form of a bird and traveling with Nephthys, Isis travels the length and breadth of Egypt in search of her husband’s body. During this time, Set establishes himself as the divine ruler and consolidates his power. Through the efforts of Isis and Nephthys, Osiris was restored, but was broken and cast down into the lands of the dead, the process of his revival causing him to become the first mummy and King of the dead. Lost in the underworld, Osiris is blind and in no condition to challenge Set for the right to rule.

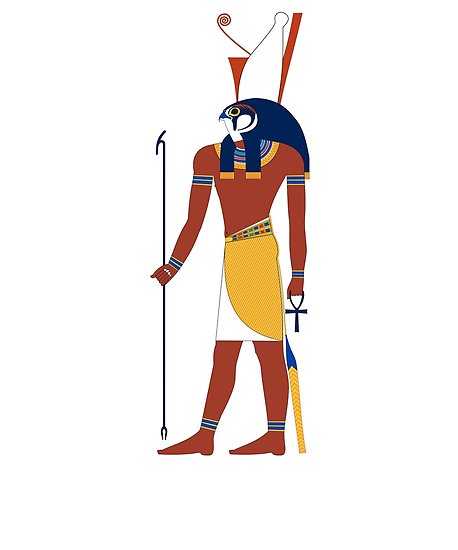

Unwilling to allow Set to get away with his treachery, Isis takes the seed of Osiris and becomes pregnant with Horus, who she keeps hidden from Set in a place of tranquility. Horus would eventually grow strong, and challenges Set for the right to rule over the gods. Over a period of more than 80 years, Horus and Set engaged in a series of challenges to determine who had the right to rule. During their trials and battles, Eventually, Horus triumphed over Set, though at the cost of one of his eyes. Much like with Osiris, the eye was separated into several pieces and had to be restored, the united pieces of the eye being called the “wedjat.” The lands of Egypt were divided between Horus and Set, with Horus reigning as the new King of the gods. They would eventually become reconciled, and unite the lands of Egypt. The Eye of Horus was restored, now called the “Wedjat” and it became a potent symbol in Egyptian myth and society. Horus travels to the underworld to restore Osiris’ sight with the Wedjat. The gift of the restored Eye of Horus to Osiris gave the old King sight and restored him, and became a part of Egyptian funerary tradition.

Symbolism in the Egyptian Myths

Egyptian culture viewed the right to rule as divine. Osiris and Set were the children of the original gods of creation (i.e. Ra) and as such they had the divine right of rulership. Pharaohs were considered avatars of these deities, and were associated in many cases with Horus, who was a protector of the gods. By adopting his mantle, they became the rightful rulers and protectors of their realm. The Wedjat, or “Eye of Horus” was an important symbol. By travelling to the underworld and giving his eye to the blind King, Horus restored his ability to see, and while the old King didn’t take his place as ruler of the gods, he was able to see and help guide his son as he took up his rulership. In this sense, Horus shows that he can preserve the old and valuable portions of the Kingdom. Succession rituals for Pharaohs emulated this practice, as a good King would have to show that he could properly respect those who came before.

Horus’ eyes were symbolic in many ways as well. One eye was said to be the sun and the other the moon, since Horus (as a falcon – a bird with exceptional eyesight) had his domain in the skies. So, in that sense, Horus’ eyes were open to the world day and night, and by giving an eye to his father, it was linked to the past in a way that could preserve (i.e. Osiris as and embalmed and preserved ruler) the lessons of the past. An eye for the past looking at the present. Osiris, the father, the old king, is saved by his son and his sight is restored by his son’s sacrifice. The old King can now see and give wisdom to the new one.

This is psychologically symbolic as well for both individuals and societies. We must also have an eye in the past so as to not forget the wisdom there that is worth saving and not repeat the errors that caused the “old King” to fall. If we don’t, we could also become blind to the dangers and be taken out by our own “Set.” Themes from this myth are prevalent in a lot of modern popular culture as well. Pinocchio in the old film travels to the underworld to save his father from the belly of a monster, a journey that ultimately proves his worth to be made into a fully individuated person (a “real boy”). Mufasa in “The Lion King” is blind to his brother’s treachery and killed, but connects with his exiled son from beyond the grave to help him obtain the rightful mantle of rulership. Leaving behind irresponsibility, Simba confronts his insecurities to depose the treacherous brother and restore the land.

How 40K Integrates and Subverts This Myth

Horus in the 40K mythology strikes a different image than Horus in mythology. Instead of restoring the kingdom, he is set up to destroy it. Instead of saving his father from blindness, he seeks to send him to the underworld. Instead of his eye being a symbol of awareness and prescience, it becomes a symbol for corruption and betrayal. Horus in 40K acts more as Set, a destroyer and usurper, who takes advantage of the blindness of the rightful ruler to depose him and remake the kingdom in his own corrupted image.

Of Warhammer’s many tropes, subversion of a hopeful story is one of the most common. Preservation of the old is taken to comical extremes, such as the Mechanicum of Mars’ fear of new technologies and strict laws against innovation. Horus’ murder of Sanguinius – a living avatar of the Imperium and symbol of hope for the future – signals the death of hope and progress. Horus is destroyed by the Emperor, but the Emperor is consigned to live on the Golden Throne, his body trapped in the darkest, deepest dungeons on Terra and his mind trapped in the “underworld” dimension of the warp to do battle with the forces of Chaos for all time.

Of course, like many things, there could be other readings to the story as well. I can hear the Chaos players out there already crying out that it is the Emperor, in truth, who is the one who deposed the true gods and sought to remake the kingdom in his image. Lupercal, who travelled to the underworld via the gate on Molech, gained insight and wisdom from the true gods so that he could restore their rule. By plunging the galaxy into eternal war, Horus has maintained the true empire, sacrificing his life (or his eye) as the symbol for Chaos and paving the way for the resurgence of chaos across the galaxy. In this reading, the Emperor is Set, and Horus is himself as the restorer and redeemer of the galaxy.

Of course, just because that reading is possible it doesn’t make it equally valid. Horus in the myth brought prosperity and renewal to the land, while Lupercal brought death, corruption, betrayal, and destruction. Horus renewed his father when travelling to the underworld, giving of himself to respect the right of rule. Lupercal sought rule for himself, looking to sacrifice others for the sake of his goal. One theory would be that Cypher is more like Horus, on his mission to travel to the underworld of Terra to use the Lion Sword to restore the Emperor, his task spanning generations of marines much like a divine hereditary succession. So, yes, you can look at the comparison of Horus and Lupercal in many ways, but while they are fun to experiment and mentally digest, not all ways are equally supportable. In fact, many are built to deliberately contradict themselves. Some are missing pieces that are fundamental to the narrative. For example, is the absence of a mother (Isis) in the 40K mythology fundamental to the failure of the Emperor’s dreams? The novel Saturnine touches on some interesting themes and has some powerful revelations that may address this, but as it has just barely been made available for general release, I won’t spoil them here.

The Applications of the Subversion of Myths

If there is a lesson to be found in this subversion, perhaps it is in how the subversion has led in part to the waking nightmare that is living in this fictional universe. Are we Horus, looking to sacrifice anything to see the world in our image? Are we the Mechanicum, so afraid of change that we reject anything new and learn all the wrong lessons from the past? How do we sacrifice an eye to the past and keep our eyes open? Are the failures of this fictional world a warning about the consequences of forgetting these themes in the real world? Or, can we be Isis and collect the broken pieces of our world and create new life from them? What would that look like in Warhammer?

An Ongoing Conversation

If you found this interesting, please check out my page Captain Morgan’s Librarius. This is the space where I test these ideas in their first drafts, and also talk about all the other parts of the hobby that I enjoy from painting, community, and gaming to all the rest. It’s also the best place to converse with me about this and many other topics in 40K. Likes and shares are appreciated. I hope you enjoyed this week’s read, and I’ll see you again next time!

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!