Welcome, 40K fans, to a series of articles I am writing about some of the deeper aspects of Warhammer 40,000.

These articles are a thought exercise, and by writing them I hope to improve my thinking about 40K and its fiction (and maybe about much more). Topics in this series will be wide-ranging and will not shy away from moral or philosophical issues that some may consider sensitive or even controversial. I would rather risk the conversation, so while you or I may not agree, I look forward to hearing why. Consider yourself warned for lore spoilers as well. Also, check the Tactics Corner for more great articles on gaming in 40K!

An Impossible Premise

This may be the hardest case I have to make, so naturally I wanted to dive right into it like a ship with no gellar field. It is likely that I’ll have to come back to this subject often, so we’ll go ahead and call this “Part 1.” That way, we can go back and see how the arguments have evolved a bit over time. For now, I am going to argue for the case that good exists in 40K, and where it manifests itself.

Starting With the Bad

There are some sayings in our community that go around that aren’t explicitly stated in the lore, but are so overwhelmingly implied that it may as well be the bedrock foundation for 40K. One of the sayings goes something like “There are no good guys in 40K.” I’m sure you’ve heard it before. If not, you’ve read it now. It doesn’t take a lot of hard thinking to accept that statement as-is. After all, we call the universe the Grimdark for a reason. War, famine, disease, bloodshed, corruption, cruelty, nihilism, vain sacrifice, and entropy are wrapped in a weighted blanket of despair in the 40K universe. Even the afterlife is tainted with the promise of eternal torment by malevolent gods. By all imaginings, 40K makes the word ‘bleak’ seem optimistic depending on who you talk to. It is a dark, awful, terrifying, and unapologetically depressing way to imagine the future, so why do we want to spend so much time there?

What can the depictions of life in this uncaring universe offer to us of enough value to not just send us into dreary fits of depression? Why would the people in such a universe even bother trying to exist at all (except, of course, for our entertainment)? And are we all so addicted to depictions of misery for our entertainment that we can just accept the nightmare as it is at face value? Are there no lessons in there for us? This may be true for some of us as readers as well (and I would recommend a good counselor if so), but I think it is a bit more nuanced than that for the majority of us.

We’ll get to that, but first we have to properly lay the groundwork for the idea that good exists in 40K, and the groundwork for that is the absolutely undeniable existence of evil and malevolence. There are many manifestations of this in 40K, but I think the ultimate manifestations exist in the forms of the main pantheon of Chaos in the warp.

The Differences Between Chaos and the Warp

While sometimes used synonymously, Chaos and the Warp are not the same thing. I will attempt to lay out my reasoning for that here. Considering how the Warp is described in a myriad of inconsistent ways throughout all the codexes and novels, I’m basically amalgamating my understanding of the warp here in a way that I think makes the most sense, and hopefully my arguments here justify why I didn’t just copy a word-for-word definition out of a codex or index. Beyond that, we are playing in the figurative realm here. Hard and fast definitions are hard to come by, and harder to nail down. Even so, not all interpretations of something are equally valid, and I hope to lay out why mine is a bit better constructed than some I have heard or read.

The Warp

The warp is a hard thing to define, much like the shape of water is hard to define. If you want to give water (or any liquid) shape, you have to put it in a vessel. Put water in a cup, and the water inside the cup becomes the shape of the cup. A beaker? Beaker-shaped water. A bladder? Bladder-shaped water. You get the picture. The warp acts much the same way, except that instead of a collection of hydrogen and oxygen atoms, you have a collection of thoughts, concepts, instincts, urges, feeling, emotions, and everything that we are aware of as fully conscious beings. Though, the water is less those things, and more like how water would taste if it were flavored by all of those things if those things had flavors. Hatred might taste like bile. Envy might taste like spoiled fruit. Violence might taste like a rotten ghost pepper, and so on.

The warp–often called “the great ocean” in 40K by the psykers who can manifest its properties much in the same way as someone putting water into a container–is a cognitive and spiritual realm that exists in another dimension outside of time that is inextricably linked to the physical realm by the consciousness of the beings living in the physical realm. Its energies manifest themselves as the concepts, thoughts, and feelings of all those who live, have lived, or will live. It is a realm of imagination that brings action and imagination into afterlife, and it often bleeds into the material realm and causes havoc. In this way, the warp is much like the ocean itself in that the water of the world collects the particles of life as it washes over reality/the world and deposits them into a briny, undrinkable ocean full of predators.

I have often heard the warp simplified in description by calling it hell. I think that is correct in some respect, but lacks finesse. It is hell in the sense that there are entities there that wait to devour or enslave your soul for time and eternity, or at least that’s the classical depiction of hell. It is also hell in the sense that conscious life made it that way, as the warp takes the flavors that the inhabitants of 40K give it–like salt in the ocean. It is the place you don’t want to be, and it is the place that you made with all of the darker parts of yourself. It turns out that there have been a lot of evil and malevolent influences on the warp, and the manifestations of that certainly helped to carve the potential of the warp into hell. That is what Chaos is, after all–the thing that makes the warp like hell.

Chaos

Khorne, god of war and violence, is a manifestation of the wars of eternity in their savagery, hate, and horror. Slaanesh is the epitome of unbridled excess and lack of self control; the never-ending hunger of indolence and privilege desensitized and desperate for meaning but looking in all the wrong places. Tzeentch is the blind pursuit of knowledge to the exclusion of morality and conscience; a selfish and covetous being obsessed with control and yet out of control as it leaves the victims of its pursuits in death and misery without a care. Nurgle is the broken, malevolent illness of our hearts that is blind to its own suffering as it spreads misery to others, it is a cycle of misery and malice that takes joy in the pain it inflicts upon others and addicting them to it like a Stockholm syndrome. There is more to say about each of these gods and what they may represent, but this short summary will serve for our purposes today. Chaos, of course, is what we could easily and accurately call the manifestation of pure evil as thought of and acted out by all conscious beings in the 40K universe past, present, and future.

Figuratively speaking, Chaos as a concept existed long before 40K, and primarily in a figurative sense. Chaos was analogous with opportunity and potential. One of the big psychological thinkers who talked about Chaos in this manner in the 20th century was Carl Jung, and I find his view on it to be particularly useful for this conversation. Jung often compared Chaos to part of the old alchemical practices of those who sought to create a philosopher’s stone, or a secret to wealth (gold) and long life. Many men considered the great thinkers of their times, such as Sir Isaac Newton, were practitioners of this proto-science.

“Jung viewed the alchemist’s efforts to create gold as a symbol of their quest to transform the adept’s soul, and he saw the alchemist’s equivalence of their prima materia with ‘chaos’ as verification of his view that such chaos is the raw ingredient of psychological transformation. The European alchemists identified this chaos with the ‘chaotic waters’ which served as the raw material for creation (Mysterium Coniunctionis, 156, 197), prior to the separation of the opposites symbolized by the ‘firmament.’ Jung understood the alchemists to hold that all material transformation and psychic healing arises through chaos, quoting the alchemist Dorn regarding the disintegrating, yet reintegrative effects of the chaos:

Man is placed by God in the furnace of tribulation, and like the hermetic compound he is troubled at length with all kinds of straits, divers calamities, anxieties, until he die to the old Adam and the flesh and rise again as in truth a new man (quoted in Mysterium Coniunctionis, 353, n. 70). For Jung, the psychological meaning of such ‘transformation by chaos’ is a confrontation with one’s personal, and moreover, the collective unconscious.”

The Red Book of C.G. Jung – Sandy Drob

This is a remarkably positive view of chaos, though no less destructive. Even so, it opens a vast opportunity for reflection on how the enemies of Chaos can be looked at in their attempts to defeat it. What if the Imperium, the Emperor, and all enemies of the warp are metaphors for a personal psychological journey of transformation, and that these storified simulations of good and evil are a ‘furnace of tribulation’ that serve to offer the opportunity for races in the 40K universe to rise again? This is important to consider, and we will in another article, but first it is necessary to prove that there is good in 40K.

The Opposite of Chaos is Order, but Does That Make Order Good?

The great enemy of Chaos, or at least the greatest enemy of Chaos by the pantheon’s own admission, is the Emperor of mankind. The Pantheon has named him “Anathema.” It’s easy to infer that they mean “opposite” by that label, but the definition has some important differences to consider, especially in the historical sense. Here are the definitions of anathema:

- a person or thing detested or loathed:

- a person or thing accursed or consigned to damnation or destruction.

- a formal ecclesiastical curse involving excommunication.

- any imprecation of divine punishment.

- a curse; execration.

So, when Chaos labels the Emperor anathema, they aren’t just saying that they hate him. They are casting him out, they are cursing him, and they are marking him for punishment. The excommunication definition has some tasty implications, because it is almost as if Chaos itself recognizes or at least one point recognized the Emperor as a peer, or a manifestation in the warp that could be as divine as they are. That is a conversation for another day.

Chaos is undoubtedly evil, and its pantheon has cast the Emperor out, curses him, and hates him. But does that make the Emperor good? Well, sort of. It makes what the emperor represents, which is ultimately order, their most hated ideal. The Emperor’s power and influence has an unmaking influence on the creatures of Chaos. It is as if the Emperor’s light and will unravels the disordered nature of the daemons of Chaos, and even the unaffiliated predators of the warp. Indeed, the Emperor’s perception as a protector, a wise king, a force for light, and a symbol of hope for a future free of the malevolence of Chaos as acted out by the uncounted masses of mankind must–by the nature of the Warp as a reflection of the thoughts and emotions of conscious beings–be good. In that sense, the Emperor’s own reflection in the warp has good elements in it, whether he intended it or not, due to the honest intentions and actions of true believers in the ideal Emperor.

Even so, too much order makes for tyranny (which is definitely bad), and there’s not much argument against the idea that even when not attached to the throne, the Emperor had a tyrannical addiction to order in his vision for what should be. You could say that the Throne of Terra was gilded with good intentions gone wrong. We talked last week about many of the myriad ways and systems through which tyranny can manifest itself. For that reason, the Emperor cannot be totally good, as he is invariably influenced in the Warp by how many people act out tyranny in his name.

A Footnote on the T’au

The T’au are like mini-manifestations of the same concept of too much order becoming tyrannical, and their ‘Greater Good’ philosophy quickly falls apart as tyranny as soon as you read about their enslavement of the Vespid, among other stories of suppression, control, and domination. Their philosophy might even be more insidious, for it in some respects robs its followers the ability to choose. Farsight’s awakening demonstrates that quite clearly. Anyone who says T’au are the “good guys” hasn’t really thought about it enough, or is deliberately trolling you.

Finally to the Good Part

Ok if the Emperor and the Imperium aren’t the good guys, what does that leave us with? Aren’t the Chaos powers also tyrannizing and trying to enslave the souls of all mankind and conscious life in the worst ways possible? So, how do we win, then? If Chaos is bad, and Order is bad, then what side are we supposed to take? Isn’t there somewhere out there that is truly good, or does good not exist at all in 40K like people are so fond of saying? How do we identify the good?

Well, if concepts such as hatred, envy, nihilism, selfishness, betrayal, and malevolence lead to evil manifestations in the Warp, what about manifestations of selflessness, compassion, love, nobility, loyalty, and honor? We can’t really expect that a universe like this, or even a race like humanity, can exist in the real world and survive without these things, and these stories have a basis in reality otherwise we wouldn’t be able to understand them. It has to make some kind of internal sense or we can’t engage in it or get invested in the stories. The evidence of human history points to a remarkable tolerance for drudgery and misery by a large swathe of humanity, of course, but not an eternal one or one without joy. People eventually rise up against tyranny, and tyrannical systems fall apart much like the Imperium does and is slowly falling apart. Yet even in the midst of the bad, people find ways to make life worth living. If the Warp is a reflection of reality, then it must also reflect the acts of good in the universe, or it doesn’t follow its own rules. Yes, 40K is very much prone to that sort of all-bad-no-good mentality by design, but again, if it was just that, it would be less engaging than it is.

I think there is a growing case to be made that good concepts exist and manifest themselves in the 40K universe in meaningful ways. What evidence of these manifestations do we have? Several, though not as many as I think are appropriate given what we understand about how the warp works. I think that as time goes on and authors (and us) think about 40K and the Warp more, we will continue to see these manifestations grow in number, though the ethos of 40K writing and investment in the theme demands that the good in the warp be limited in scope and power so we don’t have to give up our addiction to the grim darkness of the far future. They do have a brand to maintain, after all.

MAJOR SPOILER ALERT

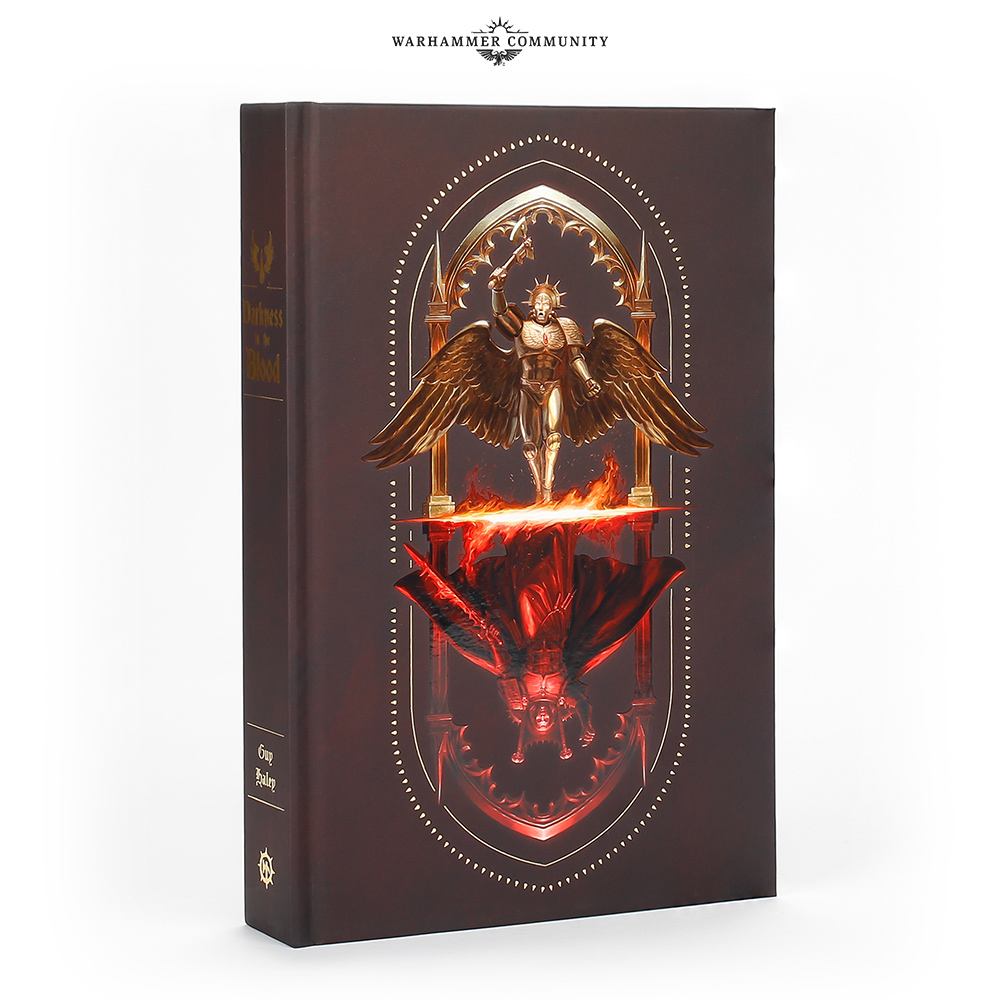

There are a few examples, and I will focus mostly on one, but consider this your MAJOR SPOILER ALERT for some material you may not have read yet. This comes from the Darkness in the Blood novel by Guy Haley, as well as Ruinstorm by David Annandale, The Unremembered Empire by Dan Abnett, and The Herald of Sanguinius by Andy Smillie. Consider yourself warned, and also encouraged to buy and read all of them.

In Darkness, there are a lot of highly figurative themes dancing about, and they center around the Blood Angels chapter of Adeptus Astartes. There is not a better example of a metaphor for psychological development and individuation than the Blood Angels in all of 40K fiction, and while you all may rightly scream the words “YOU’RE BIASED” at the screen at this comment, I nevertheless stand by it and am correct. I will explain why in the paragraphs below, but also in future articles. This is getting long, and I need a lot more space to make the comprehensive argument that my thesis as stated above deserves, but this will suffice for now.

The Sanguinor

The Sanguinor is an interesting being. The composition of the name is interesting in a linguistic sense as well. Sanguinius uses the suffix ‘-ius’ to denote ‘belongs to’ or ‘made of.’ So, Sanguinius’ name simultaneously means “belongs to the blood” and “made of hope.” In that same way, the Sanguinor’s name uses the suffix ‘-or,’ which means “the person or thing that performs [action].” This means that the Sanguinor’s name means “the person or thing that performs hope.” That’s a good thing to chew on, since names can have important meaning, and sometimes even accidentally end up adding more depth to something that was intended in the beginning.

For those who don’t know, the Sanguinor started as a proxy for Sanguinius when he was made Emperor of Imperium Secundus during the Horus Heresy. This was done mostly as a security measure to protect Sanguinius from assassination, and was accomplished by having one of the Sanguinary guard forsake his identity to take on the persona of Sanguinius. Evidently, he did so in such a complete and honest way that by the end of the Ruinstorm novel, this herald of Sanguinius (a non-psyker) began manifesting powers that gave him strength to contend with Chaos. This was manifested in his ability to contain a powerful demon prince of Chaos undivided long enough to have it blasted by planet-killing ordinance. This would have killed a normal person, but at this point the Sanguinor was more than a normal person or an Astartes. As an example of individuation, the Sanguinor took upon himself the burden of sacrifice voluntarily, and was able to transcend his current state of being after death (much like Jung describes in the quote above about the ‘new man’). The Sanguinor would go on to show himself over the next 10,000 years as a glowing angel of light appearing deus ex machina-style to rescue Blood Angels and their successors from hopeless situations.

The nature and meaning of this transformation was not described in any form of much substance until the Darkness in the Blood novel by Guy Haley, where Mephiston gets to witness the Sanguinor as he contends with another warp entity of Darkness (the Sanguinor’s opposite and all that that implies) before his eyes.

“The warp is a mirror to the material realm,’ said the bloody angel. ‘The shape of the warp is the shape of the mortal soul, If it harms us, we only have ourselves to blame… These creatures are the reflections of your bloodline. The golden angel [Sanguinor] is your purity… Thousands of years of sacrifice, denial and endless war. Every time one of your brothers creates a work of beauty, or lays down his life for those weaker than he, it strengthens the angel in gold… He was once a man, like you. Into him has poured all the nobility of your kin for one hundred centuries. See how powerful he is.”

Darkness in the Blood, 228 – 232

So, here we have evidence of exactly what I’ve been getting to with this thesis: actions of good have positive consequences in the Warp, and create beings that are manifestations of good actions in reality. To further add to the pile:

“‘The warp itself is not evil, always remember that, Mephiston. It is corrupted, but it contains everything, and that includes good as well as evil. It includes you.”

Darkness in the Blood, 233

It is fair to point out that this all happens in the warp, and an argument can be made that this conversation is tainted by that. The book itself addresses that, and that leaves us to decide whether or not we take this seriously. I contend that it makes a lot of sense and fits in with the understanding of the warp as depicted consistently across 40K fiction.

In Conclusion

Good exists in 40K in the same way that evil exists in 40K. It certainly appears to be the case that there is more evil in 40K, but that does not mean that no-one or nothing is good, or that characters or us as readers cannot align ourselves with what is good. It is important to think in those terms as well, insomuch as good is a concept we must align ourselves to and not a thing to manipulate until it serves our own purposes. Now that we know that, we can begin to ask more questions about who or what is good going forward. I look forward to expanding on this topic sometime in the future, and hope you will be there for that as well as I navigate all of this.

About BattleHaven

One thing I can unequivocally declare as good is BattleHaven.

Some of you here may be familiar with my previous articles about how amazing the BattleHaven experience is. It is coming up again this year from May 5 – 9th, 2020.

My troubles are far from over this year, but one of the things I keep coming back to is how much I’m looking forward to BattleHaven this year. Sarah, who runs the show, is an incredible host to me and my wife. We are fed well, play tons of games, enjoy the scenery, and get to soak in all the best things about being a Wargamer. What better place to discuss topics such as this than at BattleHaven? I would love a chance to sit around a fireplace and talk about the wider implications of 40K with anyone who would listen. The only thing missing? You, of course!

As it turns out, Sarah has a couple spots left to fill, so if you are interested at all in going, then get in touch with her at BattleHavenEvents@gmail.com. If you mention that Captain Morgan sent you, she’ll knock 10% off your trip package.

An Ongoing Conversation

If you found this interesting, please check out my page Captain Morgan’s Librarius. This is the space where I test these ideas in their first drafts, and also talk about all the other parts of the hobby that I enjoy from painting, community, gaming, and all the rest. It’s also the best place to converse with me about this and many other topics in 40K. Likes and shares are appreciated. I hope you enjoyed this week’s read, and I’ll see you again next time!

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!

That felt like a very round-about way to say “Good and bad both exist, and there are individual acts that are good.” Surely, there are worlds in the Imperium that have barely known war, and are people on those worlds who act in a manner similar to ourselves, leading humble lives trying to make it through the year, paycheck to paycheck, helping neighbors and being a service to the community.

But if you mean “good” on a grand scale, then no. I don’t think good exists in 40k. Even the Blood Angels have their dark side and covered-up secrets. While “goodness” on an individual level exists in 40k, none of the main players are purely good. Plus, Orks throw the entire philosophical question of goodness out the window, and then proceed to blow it up with appallingly large ordinance. To an Ork, “good” and “bad” don’t carry the same meanings as they do to us. To them, getting into a huge fight that leaves a third of everyone dead is good, and something to be celebrated by calling in twice as many friends to take part in the fun.

40k says that even when things appear good, it doesn’t take many zoom-in’s or zoom-out’s to see a more ugly picture.

So, I’ve established that good exists in 40K, but I haven’t defined precisely what that means (though I’ve laid the groundwork for that, and that’ll be in part two). I agree that 3K words is a lot to just say vaguely that good exists, but I think the foundation of my arguments going forward needed to be strong enough to hold up what the next points are.

Under the scrutiny of a perfect gaze, not even any individuals can be described as wholly good, but I don’t think that that works as a valid way of discounting the existence of good in 40K or that there can’t be a good cause. It’s a pretty harsh condemnation of not just the Grimdark universe, but also ourselves as imperfect beings to say that because when zoomed in or zoomed out enough, we really aren’t that good. Who is to say that we as viewers have a perfect grasp of what perfection is to begin with that we can judge without fault the faults in others?

The ‘everything is really bad’ theme, of course, might just be the underlying theme of 40K, but I think that’s more of a surface-level theme. I don’t think people are interested in nihilism as compelling content. That’s why I’m digging for something a bit more than that in these critiques. Hopefully this will help support part 2’s argument.

To your points about the arbitrary nature of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ from an Orkish perspective, I don’t think that’s a road that any of us can really trod with confidence. Fundamentally, Orks are written from a human perspective by humans both inside and outside of canon. They have to relate to something we can connect with. The Orks are very much like someone took the straitjacket off of the violent, suppressed id of the collective subconscious of mankind. Id is instinct, it just exists and does what it does, and acting on your id’s desires doesn’t make you good. In that same way, the Orks’ perspective on good and evil isn’t really relevant, because they aren’t developed or intergrated enough personalities to really have morals to begin with. Right and wrong don’t cease to exist or become arbitrary because people don’t understand them or have different perspectives. The world as a whole decided with the Nuremberg trials that there are just some things that people don’t get to do, no matter where they grew up, whether or not they were following orders, or whether or not their culture permitted it.

Sorry, but after the comment with the Tau and not “thinking it through enough” I have to take a step in as an historian:

The world did what with the Nuremberg trials ? The world – first of all – did nothing: Most of the world either had to take care of their own problems after the war; had no power; or had to deal with the horrible consequences. This was not an universal agreed standard (quite contrary if you look at the resulting conflicts after that).The winners decided what was right and wrong, good and evil – and no this is not some weird defense of national-sozialism, but rather to point out, that until today the legal definition of “genocide” excludes political groups since the UdSSR was involved in those agreements “by the whole world” – despite the inclusion of those groups and the concept of social genocide and genocide against political groups by the creator of the term, Lemkin.

This also includes the non-consequence of many allied attrocities (you know of at least one with quite a big bang) – again – despite many intellectuals, politicans and social groups disagreeing with that. As well as many ignored “bad” things until historians took their time digging through source materials, like sexual genocide, attrocities against many women or even just PoW’s. Again – not because the “world” agreed on it, but mostly because there was no interest or other benefits for the ones deciding over those rules (be it to allow for different genocides in UdSSR, or to allow an aggressive nuclear politic like in america until the UdSSR got the bomb themselves).

Additionally, there was mostly no way of counter-arguing (and as such no way of a mutual agreement) like in the case of the Tokyo tribunal, where many accusations and protocols were not translated or were highly delayed (again not arguing about the decisions and there quality – but rather against your uniformal concept of “the world decided”) also resulting in many forced upon terminologies: Be it the forced definition of Shinto as a religion by americans (resulting in the entire problem of the Yasukuni Shrine) against all modern definitions of the term by scholars or even the rapid ignoring of planned changes in Japan since the Japanese were now the “good guys” and the Chinese “the bad ones” (including the demilitarization, political changes for a more democratic Japan or even the persecution of war criminals).

You are ignoring the time in which this happens, where society was already starting to split into opposing concepts of good and bad with the socialist and democratic-capitalist groups, while the trials were happening, or even with individuals like Ghandi who opposed many – and I mean maaaaaaany – of the ongoing one-sided dominance of specifically the anglo-centric views of moral, religion, good, evil, state and so on.

Half the world was not even interested in those questions, since they were of no concern for them or because they were excluded (Indians starved to death; colonies are more interested in western an non-western oppression and that definition; Eastern European countries had to deal with the fact, that being thrown to the russian wolves by the western allies and the resulting genocides, deportations, and brutal hunt for intellecutals and other groups was an accepted casualty not worth mentioning – despite Nurmberg; Asia nearly completely ignores such topics and talks until today more about mass rapes, the atomic bomb and medical experiments; …)

Sorry, but IF there even is an historical example for a “universally agreed concept of right and wrong” …. the times of the Nurnberg trials are most certainly not the right timeframe.

Ok, Shinobisaru (Spymonkey, if my Japanese hasn’t failed me), excellent comment.

I think you’ve raised some fair points about how the Nuremberg trials didn’t do enough, or apply rules fairly or comprehensively. I’m not really looking to debate that particular point. The reason I brought up Nuremberg is because it is at least a step in the right direction so far as creating a transcendent human ethic goes. Certainly not a final form or a perfect execution by far, but it still serves my point well enough in that in awakening to the depravity humans are capable of, there was a point where it was said “No, nobody gets to do that anymore.” That people still get away with it or got away with it is a travesty to be mourned, but I’m not trying to make the case that it has been applied in ways that make it live up to its potential. I’m simply pointing out that it was an important step along the way to defining a human right and wrong.

I will take your claim at being a historian as you stated it. I have a deep respect for history (my father is a military historian). I grew up with bookcases full of history books, and expanded on that knowledge during college, though I didn’t make it my career. I maintain a deep interest in these topics. so I welcome your perspective.

I’m not really interested in turning this into an East vs. West historical moral debate either. Keeping this within the Western contextual view will be enough, since this is a product of the West for a largely Western consumer base and the stories are written by Western authors. I think it is fair to use a Western moral lens to judge these stories, just as I use a Western moral lens to criticize those who ascribe to Western morals and fail to live up to them. These articles aren’t apologies or excuses for imperialism or colonialism. I do contend that the “anglo-centric” views on morality are pertinent for the conversations I’m having here in these articles, certainly.

It may interest you to know that I lived in Japan for a couple of years. I learned Japanese there and I had many opportunities to discuss many of the historical perspectives between the two nations with a variety of people. I have a deep love for the culture and people I knew and served there. It was quite an enlightening experience. I’m sure we could have many interesting conversations about how history is viewed from the other side of the Pacific.

Anyway, I am prepared to admit that the Nuremberg example I used was not fleshed out as much as it could have been. I maintain that it was an important historical epiphany about right and wrong, even if it never lived up to its potential.

In any event, I’m only getting started with this series. This is part 1. I have much more to consider for part 2 in a few weeks, where I am going to try to narrow down the definition of good a bit more. In the meantime, I appreciate you giving me much to think about.

Just gonna quote/paraphrase a few things from episode 19 of If The Emperor Had A Text-To-Speech Device

“Have you ever heard the saying ‘we all have our own personal daemons’? Now, take that saying and apply it to the entire population of the galaxy.”

more poignantly

“Something which people seem to forget, even the gods themselves, is that they represent ALL thoughts and emotions. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

“For example, Tzeench may be a cruel and devious trickster, but he’s also a force for progress and a beacon of hope.Change, after all, in neither innately benevolent or malevolent, but it sure isn’t the same as it was before. Without Tzeentch there would be no malicious schemes, but there would also be no one clever enough to save people from those schemes. Nothing would ever get done and we’d fall into an eternal state of static karma.

“And THAT is what Nurgle represents: stagnancy. A lack of change, inevitable eternal cycles of decay and renewal. But he also represents the resilience, resolve, and solidarity to face those same, unsettling inevitabilities. Without Nurgle there would be no consistency, safety, or comfort in living and dying. In fact, there would be no consistency at all. And all those cycles of decay and renewal are just the circle of life. In fact, Nurgle is technically nature incarnate.

“Khorne may be a force of merciless, mindless slaughter and hatred, but that’s because he proscribes to another natural concept: survival of the fittest. Strength and skill are all that matters to him. He also represents justice, vengeance, and honor, so unlike the others, Khorne would never try to trick you and stab you in the back. Without him, there would be no honesty, and no strength to fight against injustice.

“And speaking of injustice: Slaanesh may be a horrifying, cruel, tortuous fiend that breaks minds and inflicts untold suffering, but it also exudes just as much joy, freedom, expression, and happiness. Slaanesh is formed from the extremes of emotional experience, representing both joyful freedom, as well as crippling suffering. Without Slaanesh there would be no happiness, and no grief to make the happy times MEAN anything.”

Ah, TTS. I’ve rarely come across something that manages to both be trite and thoughtful at the same time, though I will say I have some disagreements with the ideas put forward in the analysis of the warp entities.

I challenge the idea that Chaos deities are both the good and the bad. Instead, much like indicated in my source above, they are perversions of the good made manifest in evil ways. That’s what makes it so insidious. Nothing sells a lie like a twist on the truth. That is a very human experience, by the way. We have all encountered people who take a truth and twist its intent into something it was never supposed to be. It’s true enough to be believable, but it isn’t true enough to be true.

The Chaos gods live in the warp, which is the resting place of thought, feeling, and emotion, but they aren’t the warp. They are corruption made manifest. They certainly aren’t the source of honesty, strength, happiness, grief, comfort, or cleverness.

We are discussing fictional universe, right? And the only way to experience it is through the collected works of all the authors. And this body of all the fiction, images and sculptures definitely has a dominant vibe – it’s not called grimdark for nothing. So, theoretically you are absolutely right – the setting itself does not preclude acts of kindness, compassion and love. You bring it up yourself – warp is the manifestation of all thoughts and emotions that coalesce into gods and gain consciousness. Thus, it is true that there should be benevolent gods. Thing is, nobody cares to visualize them. Grimdark, afterall, is what differenciates wh40k from other space operas. This is how it is marketed, this is what the fans pride themselves on – that they can handle it.

Now, why would anybody want to imagine and come back to the dreary, hopeless universe of suffering and endless battle against overwhelming odds? My guess is that because this is how we feel ourselves, this is what we were brought up to believe. That life is struggle, that you have to make a sacrifice to count, that you have fit into the uncaring society. But even in this bleak outlook we do need stories to show us the way and heroes to tread that path. You are right to say that warhammer stories are allegorical – any story ever told is allegorical and shows a hero’s journey. Every story falls into one of the archetypes and has a certain structure. Question is, what stories do you saturate your mind with?

I would argue that the main story of warhammer is martyrdom. Look at all the skulls! They are the linchpin of wh40k icongraphy. Why? Because skull is the symbol of sacrifice. The only meaningful offering a being in wh40k universe can make is give his own life even – and most often – for a lost cause. Take space marine – an epitome of hero, a dream of superhuman, a role model. Orphaned youths psychically indoctrinated into merciless xenophobic killing machines. What do they have to give other than their lives? The only good they ever knew were the bonds of brotherhood but even those were tragicall betrayed.

Truth be told, ive been down for more than two decades, but over the last couple of years i’ve grown increasingly weary of the effects such imagery has on me. Because ultimately we are what we surround ourselves with. The object of our focus seeps into us. And i have been willingly subjecting myself to images of violence, death, destruction, hopelessness, terror, hatered, opression and xenophobia. Did it turn me into monster or a criminal – no. But there are alternative costs. Would i be a better man if i spend more time interacting with images of beauty, serenity, kindness and compassion? Definitely! The content that we consume defines our composition.

GW seems to become increasingly cautious and aware of the broader issues outside of the hobby, they’ve toned down sexual objectivation, and even brought Guilliman back – that’s the brightest glimpse of hope the grim darkness of the far future has ever known. So, maybe there are some *good* times ahead! Get me right, i was laughing my ass off when i heard about warhammer kids – this is not what i envision for this prodigal setting, but adding contrast would only make all of its elaborate details stand out. Give me hope and meaning and i will be the first to the fray!

Excellent comment, thank you!

I am picking up what you are putting down here. That’s part of the reason I’m exploring this topic. The way this story goes from nihilistic moping simulation to an engaging mythos is tied directly into how the stories draw from the struggle against the overwhelming forces of creation to survive. If 40K was just like “Waiting For Godot” then it would be much worse.

Let’s open the 8th Edition 40k Rulebook and turn a few pages past the inner liner to the first paragraph of text, where we are confronted with:… “He is the Carrion Lord of the Imperium, for whom blood is drunk and flesh eaten. Human blood and human flesh – the stuff of which the Imperium is made. To be a man in such times is to be one amongst untold billions. It is to live in the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable…”

Let’s take that for face value: “the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable…” What comes to mind is perhaps the Assyrian Empire under Ashurbanipal, pre or post Imperial Rome under Sulla or Caligula, The Mongols under Ghengis Khan, The Spanish Inquisition, the subjugation of various Indigenous cultures of the Americas by European Colonial Empires in the early modern era, and in the last century alone: Stalinist USSR, the 3rd Reich of Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, Maoist China, Khmer Rouge, ISIS Caliphate, North Korea, etc… Imagine all of these rolled into one, pumped up on steroids, and there you have the Imperium of Man, “the cruelest and most bloody regime imaginable…”

You correctly contextualize this debate in the context of our current Post WW2 paradigm and Western Democratic-Capitalist worldview, as that is the situation most consumers of 40k live in. How would the Imperium of Man fit within that context? In short, it is the definition of a fascist state. Not the pejorative ‘Fascist’ that people throw around willy nilly in political debates these days, but the loosely agreed-upon definition by historians and theorists. Authoritarian totalitarianism? Check. Rampant xenophobia, racism, and intolerance of difference, and self-justified genocide based on those views? Check. Organization of society to support endless total war? Check. Blind obedience to the state? Check. Belief in traditional values and distrust of modernism? Check… The list goes on…

So it confuses me that you would uphold The Sanguinor, the Blood Angels, or any agent of the Imperium of Man as an example of ‘Good.’ Sure, they may occasionally show traits that could be considered admirable, such as duty, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. But what are they fighting for? They are fanatically fighting for “the cruellest and most bloody regime imaginable.”

You could look at a kamakaze pilot of the Imperial Japanese – they are sacrificing their life in duty and loyalty to their family, community, country, and Emperor by crashing into a US naval vessel, and destroying a vast proportion of material and people compared to their own loss, thereby stemming the inevitable invasion and destruction of their homeland. You could say they are brave and selfless, maybe even a martyr, but are they Good?

No, they are fanatically fighting for one of the cruelest regimes imaginable by our modern standards.

I struggle to find an example of ‘Good’ in 40k, and it seems you do too.

Perhaps one could look at the Exodite Eldar, who live a basic nomadic tribal-agrarian existence in relative peace with their environmental surroundings and other Exodite neighbors at the Eastern fringes of the galaxy. They are not expansionist, live ascetic lives away from the excesses of other Eldar, and only defend themselves when attacked. However, they’ve been largely removed from the fluff, and never had any official models. Their only true representation was in the 2nd Ed. Eldar Codex. Hopefully that might change, but I’d imagine GW would rewrite them to be more aggressive in order to justify their participation in the genocidal grim dark.

So let’s be real here and take the background of our beloved universe for what it is.

“…War is Hell” – William Tecumseh Sherman.

There is absolutely nothing positive about Hell, or war, or a galaxy defined by being consumed by it.

And the pain depicted in this human drama is one of the reasons why it’s such an appealing fantasy playground to romp around in.

Excellent comment, thanks for joining the conversation!

You bring up some very good points. The 40K universe is deliberately crafted to be the largest exaggeration of the worst things we could imagine. It is harder to find the good in 40K because it is made to be as awful as possible. As you pointed out, it took 3K words just to establish clearly that good can exist in 40K.

That said, I absolutely can justify defining the Sanguinor as good, because that is exclusively what he is made of.

” The golden angel is your purity… Thousands of years of sacrifice, denial and endless war. Every time one of your brothers creates a work of beauty, or lays down his life for those weaker than he, it strengthens the angel in gold… He was once a man, like you. Into him has poured all the nobility of your kin for one hundred centuries. See how powerful he is.”

The Sanguinor is a living concept made of the highest ideals. It is also only one half of the story. In this story, there is a darker angel that is made of all of the sins of the BA chapter, and the two angels are in contest with each other. The injustices committed and supported by the BA are represented in that living symbol. You’ll notice that I didn’t say that the BA were wholly good or a pure example, simply that the Sanguinor is good, and that his existence as good in 40K and as a living construct of higher ideals means that other manifestations of those good ideals must exist as well.

You are making an important point when you talk about ideals like honor, bravery, loyalty, etc. appear in the context of the cause that they serve. I have some experience with the Japanese and their perspectives on WW2 (or lack thereof). I lived there for a couple of years as I’ve mentioned in other comments. Unfortunately, except for a few specialists, most Japanese aren’t aware of more than a surface level of history of the time after their war with Russia close to the turn of the 20th century. The WW2 time period for Japan was extremely complicated, and the Japanese are very complicated, but if I can be forgiven for simplifying things a little, the Kamikaze was a person viewed like a tool who was excellent and full of potential but misused.

You could probably say the same thing about some Astartes chapters. Probably about most, really. Some, like the Salamanders or the BA are definitely more altruistic and serve a higher noble and try to act as if the highest ideals of the Emperor were made real in their actions. The beauty of 40K is that you can make your actions real in the warp. You rightly point out that the BA have a dark side, but I must quote one of the best lines in fiction I’ve heard/read as food for thought in that context:

““What is better? To be born good, or to overcome your evil nature through great effort?” – Paarthunax

That ‘overcoming your evil nature through great effort” ties into a lot of the transhuman and individuated ideals that are where I think good exists in 40K. Concepts can be pure, sure, but people aren’t living up to their full potential until they’ve overcome themselves. To put it in Jungian terms, you have to integrate your shadow to become the “new man.” There are some very literal representations of this in 40K.

I’ll expand more on this idea for part two.

Thanks for your thoughtful response Chris, looking forward to your next essay, Cheers!

Completely unrelated to the article, but I do ship Sanguinor and Celestine.

exsellent!!