Charlie here from 40kDiceRolls, here again, to discuss something a bit different – mathhammer and expectations. As always, for more tactics articles, check out the Tactics Corner!

One smelly tournament player to his opponent: “I can’t believe my dice today! I should have killed WAY more stuff this turn.

Opponent, wearing an appropriate amount of deodorant, the model of all tournament players: “What do you mean?”

Smelly: “I should have killed like, I don’t know, 3 or 4 marines on average at least. Space Marines are OP!”

[Charlie, popping up from nowhere ala Adam Connover]

Charlie: Well actually, average rolls are rarely seen in reality and your math is all wrong! Hi, I’m Charlie and this is Charlie ruins mathhammer.

[Theme music]

Close your eyes for a minute and picture this scenario. Player A controls 10 space marines and Player B also controls 10 space marines. Everything has BS3+ S4, T4, W1, AP0, D1, Sv3+, and let’s assume each marine gets 1 shot. If Player A’s space marines shot at Player B’s space marines, how many space marines would die, on average? Well, it turns out, just one. A little less than you thought? Let’s walk through how we calculate this.

We start out with 10 shots of which 66.6% hit (BS3+), leaving us with 6.66 hits. Of those hits, half wound (S4 versus T4), leaving us with 3.33 unsaved wounds. Thanks to the Sv3+, on average Player B will make 2/3 of his saves, failing 1/3 which means that 1/3 of 3.33 marines die. In other words, 1.11 space marines die on average.

Why is this important? In a game that largely revolves around killing stuff to win points or killing stuff to remove it from the board and thus take away points from your opponent, having a good idea what affect specific firepower will have is important. Turn by turn over the course of a game, you’ll have opportunities to allocate firepower from different units to different targets, or even split up shots within a unit. Knowing when you’ve diluted your firepower across too many targets can save you headaches down the road when that unit you targeted just barely survives to hold some important objective.

Smelly: “OK, so I’ll always kill one marine when shooting with ten marines, got it.”

Charlie: “Hold on there, that’s not right either. See that’s what you’ll get on average, but the average is far from guaranteed. Statistically speaking, you’re more likely to not kill one marine than to kill one marine.”

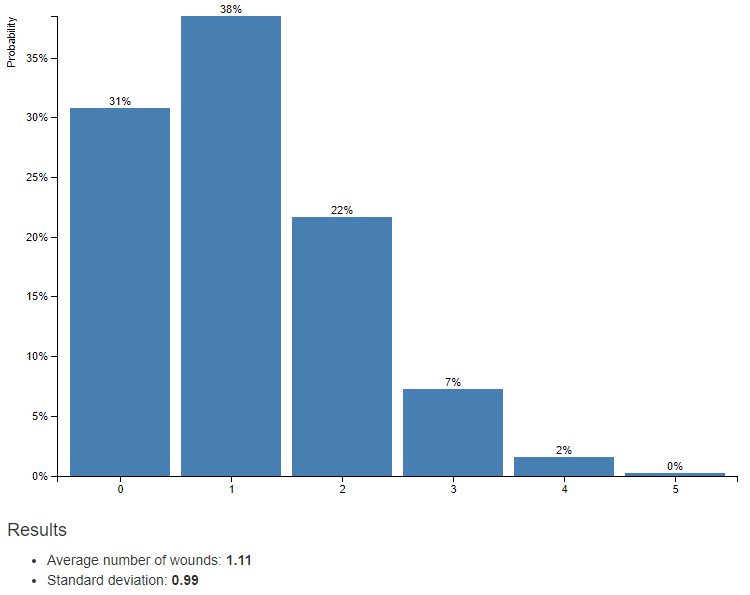

This is where variance and standard deviation comes into play. Let’s take a look at this graph, which shows the statistical probability of killing 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 marines in the above scenario.

You can see that the probability of killing 1 marine is the highest, at 38%. But the probability of any other outcome combined is far higher, at 62%. So you can see that while killing one marine is that average, based on average rolls, you’re more likely to not kill one marine (as in, kill any of 0, 2, 3, or 4) than you are to kill the one marine. Check it out for yourself, here.

In actuality and in the middle of a game, knowing the probability, exactly, of the above is probably more detailed than you’re able to quickly obtain. But it’s important to keep in mind when you roll over or under the average and start to get disparaged by what you interpret as your luck for the day. Don’t go on tilt after a few bad (below average) rolls. It’s actually fairly likely.

Smelly: “Ok, so I probably won’t roll average. How is this supposed to help me then?”

Charlie: “By setting your expectations accordingly.”

Even though most of us don’t whip out our TI89-Titanium every turn, it can be fairly useful to run through a few common scenarios when you’re making lists. By calculating the odds of the outcome of your firepower against several common target types (GEQ, MEQ, Tank, etc.) you can get a pretty good feel for what sort of firepower is needed to take out specific targets. The more thinking you can do before the game, the less you’ll have to do and the less you’ll be stressed out during the game.

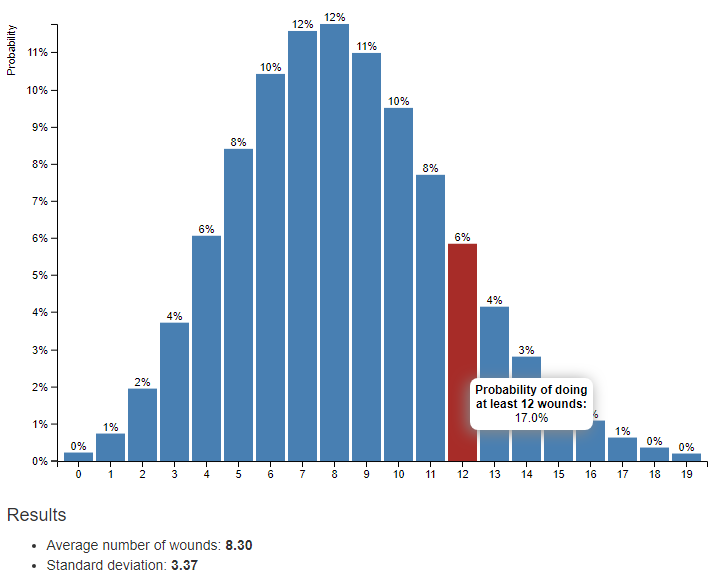

Here’s a real example from my most-current game. I was playing Death Guard and Daemons against a pure Astra Militarum force. I had a Plagueburst Crawler right on top of an objective, being a general thorn in my opponent’s side. He had several units with multiple plasma-wielding guardsmen and was determined to gid rid of my PBC. He had all 14 plasmas within rapid-fire range for a total of 28 shots and most (we’ll assume all for the actual math, Veterans, etc.) was hitting on 3’s. He only managed to do 6 damage to the previously unwounded PBC and later expressed that “I thought I had enough plasma to take it out for sure!” How likely was this scenario?

It turns out, his result was just about average, slightly below. There’s about a 79% chance that he would do at least 6 wounds. But the odds of him destroying it and doing all 12 wounds with that number of shots and that BS? Only about 17%. I haven’t played Death Guard against my buddy too much, and I think he’s still getting used to having to factor in Disgustingly Resilient. As we can see, if we stop factoring in Disgustingly Resilient, his expectation of killing it is around 61% likely, doing 12 wounds is the average result, and these results much closer match his expectations.

Smelly: “So…If I want to prepare for a game, I should make sure my expectations are realistic?”

Charlie: “Exactly. By understanding the effect an ability like Disgustingly Resilient can have on the outcome, you can plan accordingly and hopefully win more games!”

Smelly: “Or, I can just play Death Guard because Disgustingly Resilient is so strong! I can do it! I was born for this!”

Charlie: [catching a whiff of Smelly] You’re not kidding!

How often do you use mathhammer? When do you find it useful?

And remember, Frontline Gaming sells gaming products at a discount, every day in their webcart!

Mathhammer is fun as hell, for a given mindset at least (in which I share). Dice probability has a fun mix of intuitive and surprisingly complex and I’ve spent many an hour coding or just filling out spreadsheets of mathhammer. That said, it can be a bit of a vice as you say — not just due to tempering of expectations, but also because mathhammer addicts tend to ignore range, resilience, mobility, opportunity costs, likelihood of buffs actually being applied and whatnot when calculating sheer theoretical average damage versus cost. Which tends to make some units look far better or worse than they are in reality and help propagate many of the myths you see in online 40k circlejerks, not that theorycrafting stuff like the Flawless Disco isn’t still fun.

I absolutely agree. When I first started playing 40k, I immediately got super into mathammer and Tau. When I was told that the movement phase wins games, I had no idea what that means because I could calculate the most efficient units, damnit! What use did I have for the movement phase?? Since then, I’ve learned a bit 🙂 Mathhammer is definitely a double-edged sword. It is actually useful, but it’s not the whole picture.

As an avid mathhammerer, I noticed a lot of people treating those who math it out poorly due to bad stereotypes. “Oh, you think math is the only thing that matters” and such is often said. However I’d suggest to those who say such things: don’t expect someone who was capable of creating this big spreadsheet to be an idiot. Damage and Durability are what’s being calculated. Here’s what’s not: speed, range, non-damage/durability abilities, reliability, leadership, synergy, role in the army etc… These are all variables in what makes a unit good. If someone does all this somewhat complicated work to find out 2 of those variables – you don’t think that person is aware that other variables exist or take them into account? Mathing out damage and durability always helps to make a more informed decision.

Hopefully, that’s the case, that they factor in the other relevant variables as well. But I can speak firsthand about myself and how point efficiency was the only thing I looked at initially, which lead to a very skewed perspective of the game lol

Mathhammer nerds do sometimes get a bad rap. What I find interesting is that certain armies tend to attract certain personalities and that T’au, in particular, seems to attract mathhammer nerds.

Great article, Charlie!

Thanks, Reece 😀

Great article man. I think it’s really easy in the introductory concept of math hammering to get sucked into the thought of it being a 50/50 shot to hit the statistical average, and forget about the sum of the other possibilities. That 10 man space marine example lays that out nicely, and helps to prevent going on tilt when one of the outliers from the mean occurs.

With regard to math hammer players getting bagged on? Well, yes, movement, durability, synergy, roles, etc. tend to add up to more than the sum of their parts, and are huge factors. Buuuuuttt, if you aren’t calculating your odds of finishing off a unit, and efficiently allocating your damage output (target priority), you simply aren’t going to play competitively. If that’s your bag, cool, but you bet your ass that top players are doing it as a natural part of play.

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed it!

In another comment, I referred to mathhammer as a double-edged sword and I think that’s still appropriate. It’s a great tool for doing what it does, but if you don’t understand what it really does, it can create some misconceptions that might ultimately lead to frustration, which is not what anyone wants.

Nicely written 🙂 I always enjoyed putting all those statistics lectures to use, by calculating odds for 40k or optimising WoW equipment.

A lot of people I know tend to give up prematurely because they do not see their chances correctly. They assume, just cause they performed badly (in their eyes) in a turn it will be like this in the 4 following ones, too. If you know the law of large numbers you know that everything will even out over time. But you also will know that having only one Lascannon and firing it only 5 times in a game will subject you to the whims of Lady Luck much more than firing 90 shots with Pink Horrors. 🙂