Darklink is here with an editorial on the OODA Loop and how that applies to 40K.

Lt Colonel Boyd is probably not a name you’ve heard before (unless you’re USMC), but he’s one of the most important military theorists in recent times. In particular, the USMC has based much of its doctrine on some of his theories. The basic one that I’d like to discuss is his idea of the OODA Loop.

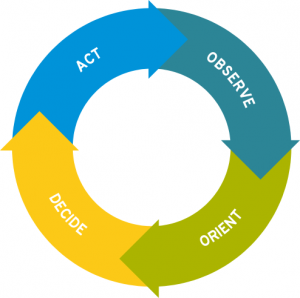

OODA is an acronym for Orient, Observe, Decide, Act. It’s actually pretty self-explanatory. In any given situation, a person reacts by first orienting themselves to their surroundings, then observing the situation and gathering information, using that information to make an informed decision, and then executing that decision.

That in and of itself doesn’t seem particularly useful. It’s more of an observation than a proposed theory, really. It’s the implications of gaming this mental cycle, or loop, from which the theory arises.

Consider any sort of competition. In Boyd’s case, it was dogfights, as he had a reputation for being an extremely good pilot, though he never actually had any kills (this was Korean war era, btw). The basic idea can be applied to pretty much any competition.

Let’s say competitor A makes the first move. Competitor B now cycles through his OODA Loop, observes his opponent’s actions, and decides on how to react. Competitor B makes his move. Now it’s A’s turn to orient, observe, decide, and act. So on and so forth, until the competitor with greater skill comes out on top. Simple, right?

Not really. The whole point of Boyd’s theory was that in order to win, you didn’t play this nice little your-turn-my-turn game. You cut off your opponent with your next move before he could complete his OODA Loop and respond, then he’d have to restart his thought process, but then you’d act quickly and cut him off again and again and again, until your opponent is left sitting there looking dumb while you maneuver circles around him. Which brings up two important concepts, Speed and Tempo.

Simply put, Speed is the speed at which you and your forces can accomplish a particular task. How quickly can your fighter pull off a barrel roll, or how quickly can this unit seize and secure that bridge across that river. Speed is an isolated, single case of accomplishing a particular task very quickly.

Tempo is the subsequent application of speed to consistently outpace your opponent and catch him with his pants down. It’s not good enough to be one step ahead of your opponent once, and then coast from there. Once you’ve gained the advantage, press it. Don’t let up. Why be one step ahead of your opponent when you can be two or three or four or five? Tempo is one of the most important concepts, strategically, in modern warfare. To relate, here is a quote from Lt. Colonel Ferrando in Generation Kill: “Gentlemen, what does Ferrando think? We have allowed the enemy to dictate the tempo of our movements. If it were up to Ferrando, we would not have stopped at the bridge this afternoon. We’d be through that city. But the good news is, once we clear the Euphrates, General Mattis informs me that we are going to be in the game, gentlemen. And when we play, we, not the enemy, are going to dictate the tempo. Once we’re over the river, we’re going to detach from the RCT, push north, and flank or destroy anyone who tries to stop us. All right, that’s it for now, gentlemen.

For those who haven’t seen Generation Kill, it follows a unit of Recon Marines at the tip of the spear of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, based on the book Generation Kill. The book One Bullet Away covers many of the same events, as it happened to be written by one of the platoon commanders in the same unit. Over the course of the invasion, the Marines are subjected to constantly changing orders, objectives, and rules of engagement. One day they’re training to take a particular bridge, then the next day halfway to the bridge they’re re-assigned to take an airfield instead. The Marines, being Marines, get the job done, but not without quite a bit of explicit language.

Then, near the end of the series, it’s revealed to the reporter that many of these orders were not nearly as nonsensical as it appeared from the receiving end. Turns out, the whole purpose of this Recon unit’s chaotic advance was specifically to keep the enemy guessing. Higher command trusted the Marines to get the job done even if they didn’t know the whole story. But because their movements were so random and chaotic, the Iraqi Army couldn’t effectively plan a means to counteract the Marines. As a result, a single company of Recon Marines seemingly randomly driving around in the middle of the desert tied down an entire Iraqi division (if I recall correctly, or maybe a battalion, either way they tied down many times their number), rendering a large portion of the enemy’s forces utterly useless. The Marines not only embraced the chaos and fog of war because they knew they could handle it better than the enemy, but they actively created chaos. This was such an important aspect of the Marine’s plan that Gen. Mattis’ callsign during the invasion was “Chaos”. Take a step back, and you realize this is exactly what Lt. Colonel Boyd was talking about with his OODA Loop. The Marines operated at a tempo that outstripped their Iraqi opponents, and as a result the Iraqis struggled to react, let alone provide an overall solid resistance.

But what does any of this have to do with 40k? 40k, after all, is an I-go-you-go system. How can you operate at a faster tempo than your opponent if you each get an equal number of “moves” each game?

It all comes down to planning ahead and making good decisions. To use an example from chess, another I-go-you-go system, a ‘fork’ is a move in which your piece is positioned such that it threatens multiple enemy pieces. That way, even if your opponent moves one piece, you can still kill the other. Similarly, a skewer is a move which lines up two enemy pieces, forcing your opponent to either move out of the way and let you take the second piece, or keep the first piece up and sacrifice it to protect the second piece. In both cases, the advantage wasn’t gained by the literal speed at which the moves were executed, but from how carefully each player had thought out their next moves.

40k allows for an even greater advantage in this area than chess, for two reasons. First, you create your own armylist. Alpha strike armies are actually a perfect example of how to plan to outpace your opponent. The whole idea behind, say, a Drop Pod army is that you start off the board, then come in turn one and blow away a large enough portion of the opponent’s army that they can’t effectively recover. There’s fast operational tempo for you right there, at least during the first turn or two. It is possible for a good player to make some clever moves and regain control and outplay the Drop Pod player, winning the game in the end. Secondly, unlike chess you have much more control over how your forces are deployed. Again, a Drop Pod army goes into reserves in order to ensure that it comes in and strikes at the enemy first. Right from the start, there are several ways in which you can place yourself in an advantageous position.

It’s important to note that you can’t let up on your opponent, however. A good deployment only buys you an advantage in the first few turns. And opponent with a well-designed army should be mobile enough, or have adequate indirect or long range firepower, to recover from being out-deployed, if you fail to capitalize on a solid deployment. It’s not enough to sucker-punch your opponent. In a truly competitive game, you’ve also got to kick them while they’re down. In a polite and sportsman-like manner, of course.

Similarly, alpha strikes are only one of many examples of how to gain an early edge. If an alpha strike army fails to cripple the enemy, it can often find itself in an exposed and vulnerable position, and it is an entirely viable strategy to design a defensive army durable enough to tank an alpha strike, then take advantage of the exposed and vulnerable enemy units trickling in from reserves (in the case of a Drop Pod army). This is one good reason to still take Rhinos. You might lose a couple killpoints and maybe first blood, but the cheap Rhinos can act as a sort of ablative armor for the parts of your army that actually matter.

It’s also a good example of why Eldar fare much better than Tau with LOS blocking terrain. Tau generally lack mobility, with the general exception of Riptides (Crisis Suits are mobile as well, but not as common competively, at least not in large numbers). Eldar, however, are extremely fast and mobile. LOS blocking terrain provides a means for opponents to hide from Tau fairly easily, and late game Tau will struggle to move out of their deployment zone and grab objectives if they’ve failed to shoot their opponent to pieces. Eldar, on the other hand, can move around the terrain, and take advantage of it as much as their opponent does, never giving their opponent a break. Eldar Jetbikes in particular become extremely difficult to deal with, as they can hide very easily and then turbo-boost onto objectives to contest or control whatever their opponent has. As a result, even up to the end of the game, the Eldar’s opponent will still be left with multiple fires to put out, and if they fail to do so they will lose on objectives.